Jesus Zaldarriaga has a checkered past. It's checkered with good deeds and bad behavior. Good grades and bad luck. Tears of grief and tears of joy. Swirling dark clouds and smooth silver linings. If anyone could turn a lemon into lemonade, it's Zaldarriaga.

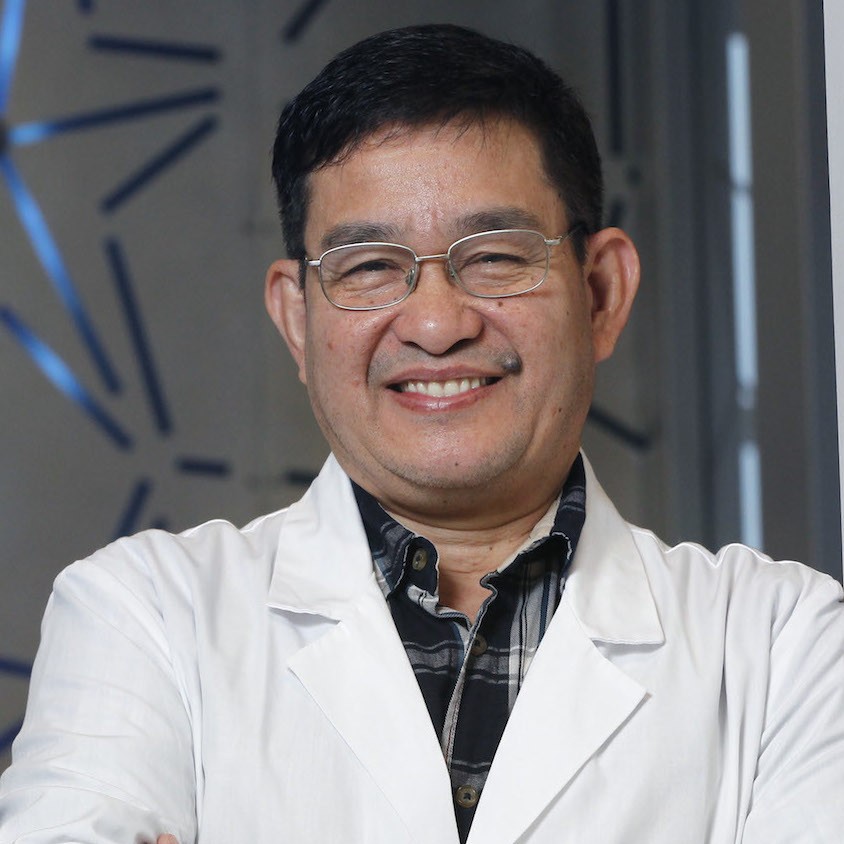

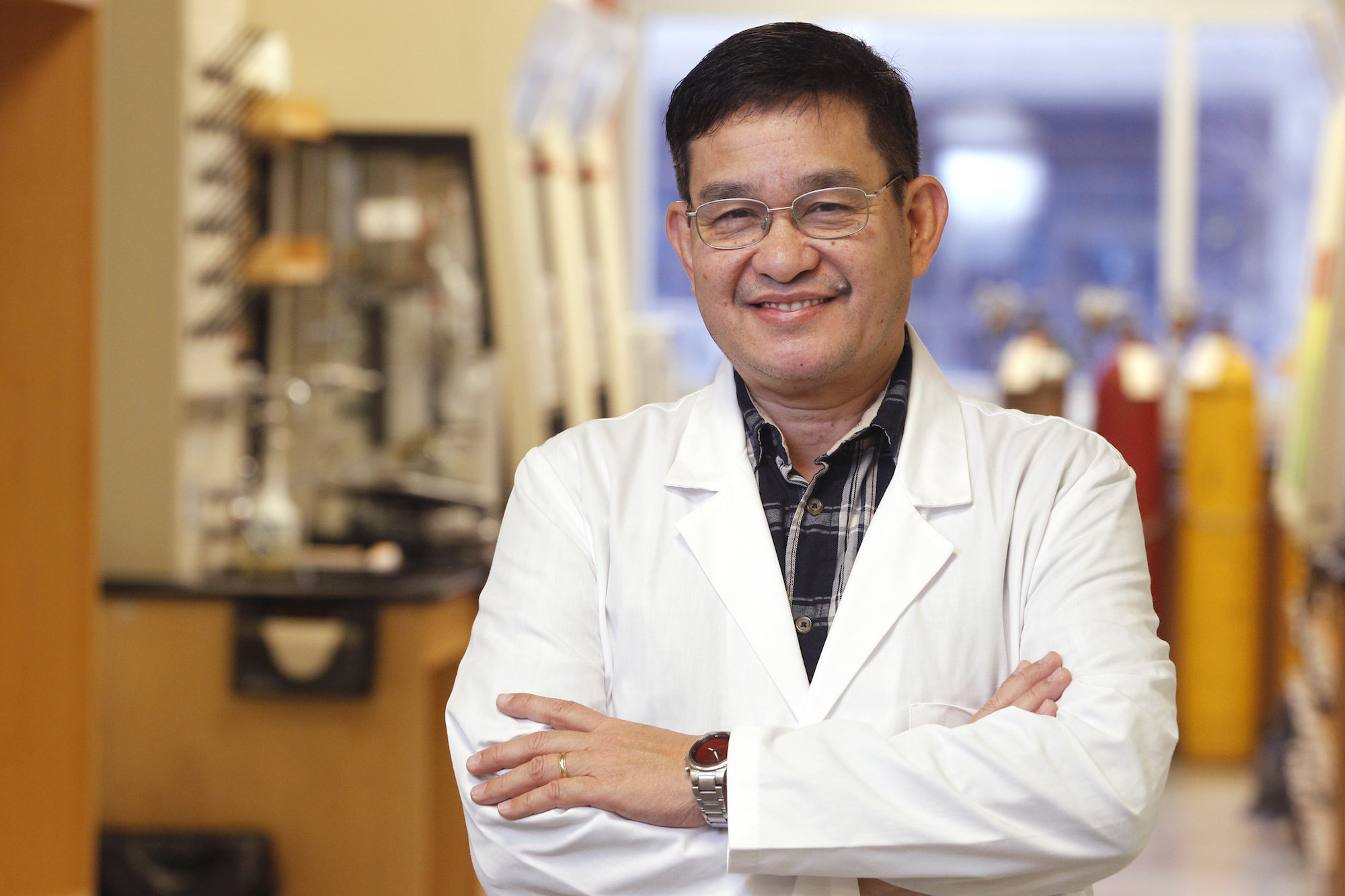

These days, when you meet Zaldarriaga, its pretty much impossible to believe that the 53-year-old man has ever done — let alone overdone — drugs or alcohol. In fact, you don't even notice his limp at first; his smile is such a warm, happy-to-meet-you hug.

And with good reason. Zaldarriaga is graduating from Iowa State University Dec. 20, not only with a diploma in hand, but also a good job in Iowa and a plane ticket to his homeland. And that’s where his story starts … in the Philippines in 1977.

A young man's dream

Zaldarriaga’s dream was to be a pilot. Growing up in a family that valued education, he made excellent grades in private schools. In 1977, he entered the aeronautical engineering program at Manila’s FEATI University. Zaldarriaga looked forward to his third year when he would fly, take parachute jumping and paratrooper classes.

In his second year, Zaldarriaga was in a car accident. Although it was difficult at the time for him to accept his doctor’s words, it really “was a blessing in disguise.” The doctor had discovered a tumor in his leg.

“I was heartbroken because you can’t be a pilot unless you are 100 percent physically fit. It didn’t hit me at the time that I was lucky the tumor was found before it was too late,” Zaldarriaga said.

The potentially malignant tumor was removed. But due to limitations in Filipino medical technology at the time, Zaldarriaga was left without a kneecap or socket. They were replaced with metal and bone grafts. He was only the second person to undergo this surgery in the Philippines. After five months in a body cast and subsequent therapy, Zaldarriaga could walk again. But he would never be able to bend his right leg again. And his opportunity to be a pilot was gone forever.

After five months in a body cast and subsequent therapy, Zaldarriaga could walk again. But he would never be able to bend his right leg again. And his opportunity to be a pilot was gone forever.

Bad times and good

Like so many young people do when their dream explodes, Zaldarriaga crashed and burned along with it.

Despite his continued partying, he got a degree in accounting. In 1984, he moved to Virginia, where his brother was stationed in the Navy. He found a job, but after six months decided “Virginia was too cold.” He joined family in Los Angeles.

Zaldarriaga was still drinking and involved with drugs in California. He hated his cubicle job as a bookkeeper, but fell in love and married Dorothy, a Filipina he met on the job. Even after the birth of their son Jeremiah, Zaldarriaga continued his substance abuse. Sometimes he was away from home for days at a time.

Still, he was able to start his own business. His wife gave birth to a premature baby who was hospitalized for three months but didn't survive. The medical expenses bankrupted the family; he lost the business. A second premature baby died. When another baby was born premature, they were told she would not make it.

“But Selah survived. She weighed only three pounds, 11 ounces at birth, but defied all predictions and lived," he said.

Turnarounds

In 1991, Zaldarriaga met a Filipino pastor who "shared Christ with me and I was saved by grace,” he said. It changed his life. Without further ado, Zaldarriaga got clean and sober.

When the economy turned sour after 9/11, he was laid off. Family told him Winnebago in Forest City, Iowa, was hiring. The Zaldarriagas moved there and thrived. They became active in their church. Their son and daughter “were like free birds riding their bikes and running around” in the low-crime, small town. They did well in school.

Hired by Winnebago as a cabinetmaker, Zaldarriaga was promoted to material handler. He earned a good living for six years and thought “it was my destiny” to work there until retirement.

But the luxury-goods manufacturer suffered during the 2008 recession, laying off a third of its 3,000 employees and closing two plants. Although Zaldarriaga found a temp job, he was laid off again three months later when the plant moved to Mexico.

Family bonds

A counselor at the Iowa Workforce Development office suggested he go back to school to acquire new skills. He chose the welding program at North Iowa Area Community College, but excelled in his science, computer and communications classes. Zaldarriaga's advisor suggested he continue for a bachelor’s degree.

“I was scared. I thought I was too old. I hadn’t had math for 25 years,” he said.

Hired by Winnebago as a cabinetmaker, Zaldarriaga was promoted to material handler. He earned a good living for six years and thought “it was my destiny” to work there until retirement. But the luxury-goods manufacturer suffered during the 2008 recession.

Zaldarriaga’s daughter Selah — a senior in high school at the time — tutored him in algebra. The math started to come back to him. He stayed on at NIACC, majoring in chemistry.

“I developed a passion to study chemistry. It’s such a part of our every day life — when you cook, there’s a chemical reaction, when you take butter out of the refrigerator, there’s a chemical reaction,” he said.

When Zaldarriaga graduated with honors, earning scholarships from Phi Theta Kappa and ISU, his daughter also earned an associate’s degree. They walked across the stage together at their 2012 NIACC commencement ceremony, then both enrolled at Iowa State.

Challenging and supportive

At one point, all four Zaldarriaga family members were in school at the same time: his daughter, an ISU biological and pre-medical illustration major; his wife studying at PCI Academy in Ames; and his son, a business major at Waldorf College in Forest City. Zaldarriaga, his wife, daughter and two dogs have lived in a campus apartment in ISU's Schillitter Village for the past two-and-a-half years.

Although Zaldarriaga thought he would excel as a chemistry major at Iowa State, he was at first overwhelmed by “challenging classes.” He found a helpful, caring community through ISU’s student support services, especially the Vocational Rehabilitation office and the TRIO program, where he "got a lot of encouragement and financial support that helps keep me going."

And he is grateful for the two chemistry scholarships (the Dr. George Felton Scholarship and the Leroy Edward Phillips Scholarship in Chemistry) he has received.

He found a helpful, caring community through ISU’s student support services, especially the Vocational Rehabilitation office and the TRIO program, where he "got a lot of encouragement and financial support that helps keep me going."

"I think, 'Wow, these people have entrusted me with their funds, so I have to give it my best and not take them for granted,'" he said.

Graduating grandpa

This fall, Zaldarriaga landed his new and improved dream job as a chemist. It was his first application and interview (what he calls his "hole in one"). After talking with a recruiter from Cargill during an ISU Career Fair, the corporation invited him for a second interview. Two days later, they offered him a job as a quality management chemist in Cargill's Eddyville plant. He starts Feb. 3.

Now a grandfather to Jeremiah's 16-month-old daughter Kayza Rose in Forest City, Zaldarriaga looks forward to staying in Iowa. He wants to stay close to the family and faith community that have kept him going and given him "a lot of strength" during his five-year journey from laid-off material handler to chemist.

Zaldarriaga will wait until May to participate in the commencement ceremony. That way, he can again "walk" with daughter Selah, who will graduate from Iowa State then.

Oh, and that plane ticket? It's her graduation gift to him. ("I cried when she gave it to me.") Zaldarriaga has not been back to see family in the Philippines for 28 years. While there, he and his wife will look for property to build an orphanage for abandoned children at risk for human trafficking.

"God blessed our lives, so we want to do this."

This story was written by Teddi Barron for the Iowa State University News Service.