As storms sweep across a landscape, forecasters have mere minutes to predict their direction and intensity — and to issue warnings to the public. To meet the extreme time constraints, they need the latest meteorological tools — tools developed by researchers who rarely experience the urgent situations they are used in.

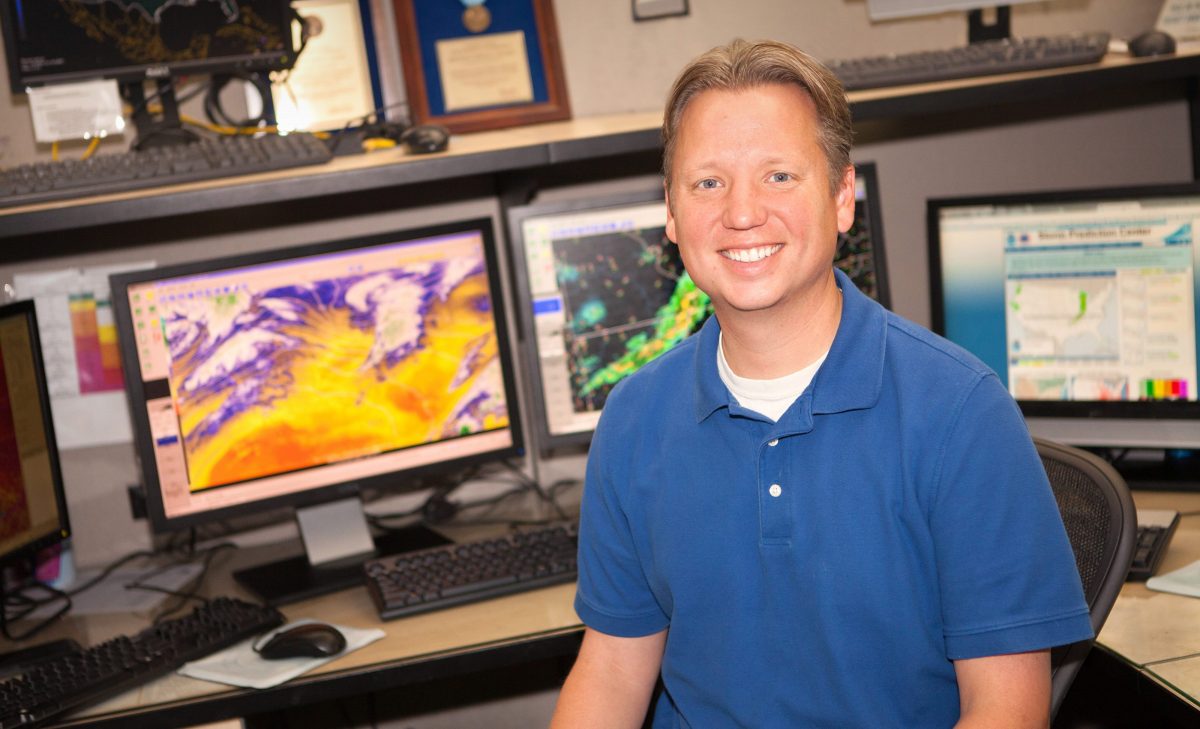

But one unique learning environment, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Hazardous Weather Testbed, led in part by Iowa State alumnus Adam Clark (’04 BS, ’06 MS, ’09 Ph.D. atmospheric science), exposes researchers to the fast-paced work environment where their tools are used.

The testbed is a once-a-year experiment that brings together the NOAA National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center (SPC) — the nation’s primary severe weather forecasting service, with the National Severe Storms Laboratory (NSSL) — NOAA's federal research laboratory studying weather radar, tornadoes, flash floods, lightning, damaging winds, hail and winter weather.

Clark, a research meteorologist at the NSSL, leads its involvement in the experiment.

Clark has been a self-described “weather nerd” since growing up in Johnston, Iowa, but even after years of obsessively watching the Weather Channel, he did not enter college imagining he would be leading both forecasters and researchers into the future of forecasting technology.

“I experienced the floods of 1993 in Des Moines and it was fascinating to me that could happen,” Clark said. “I would get up on the roof and watch storms come in. But I didn’t actually decide to major in meteorology until I took an intro class. Once I did that I realized — this is really cool. I need to do this for my job!”

Today Clark leads both researchers and forecasters through the most realistic learning environment and testing ground for meteorology research, the Hazardous Weather Testbed.

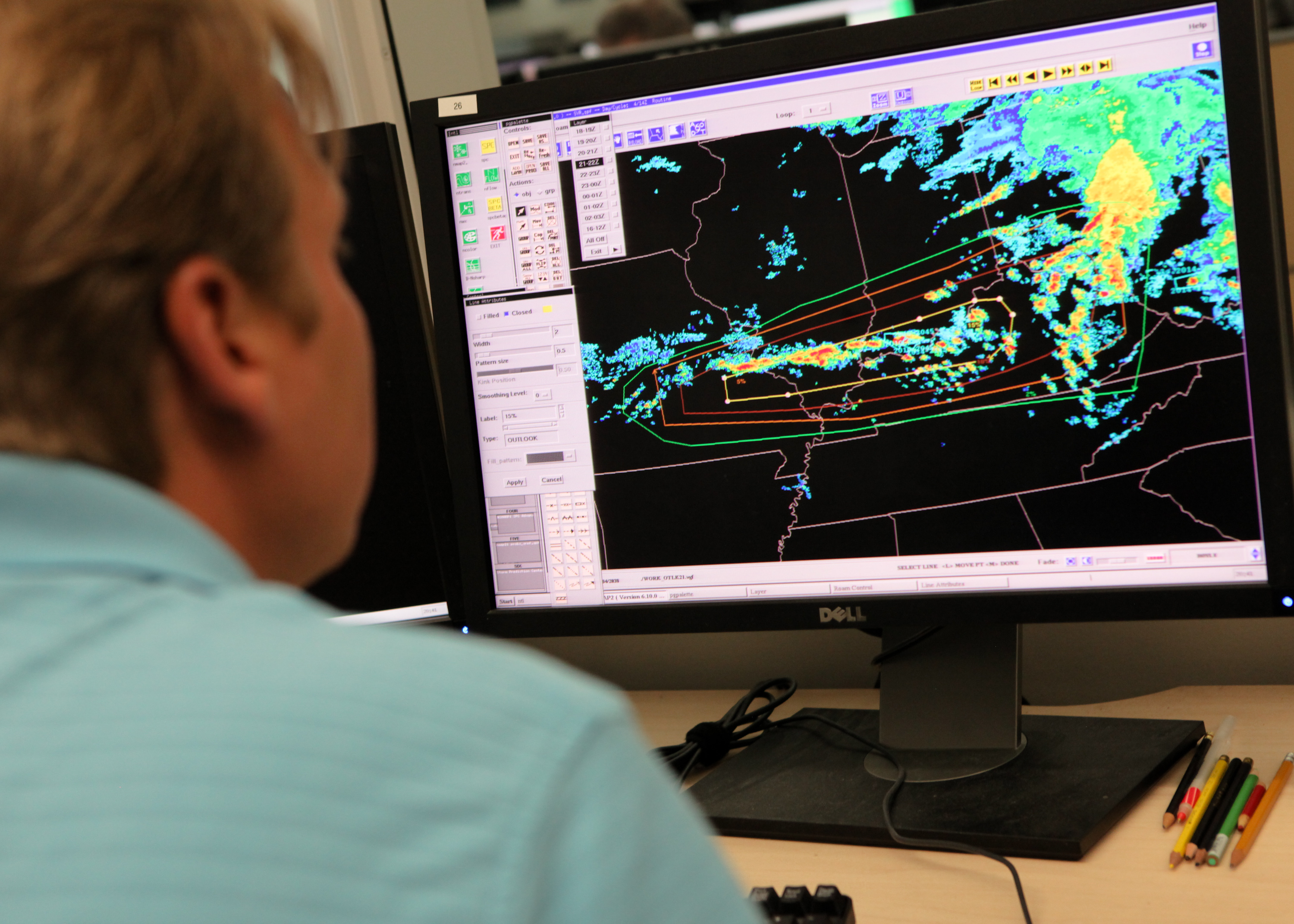

The testbed occurs each year for five weeks in the spring, when severe weather is most likely to strike. Participants choose daily U.S. locations with high chances for severe weather, then operate just like a real forecasting agency, evaluating real-time weather data, making predictions and issuing alerts.

“It’s kind of fun because while we’re in there we don’t know what is going to happen. We don’t have the answer ahead of time, so you really get to experience what it’s like,” Clark said. “You experience the same sense of urgency that a real forecaster would experience.”

But there are key differences — those in the room are a mix of forecasters, researchers and students and they have access to the latest tools in research development.

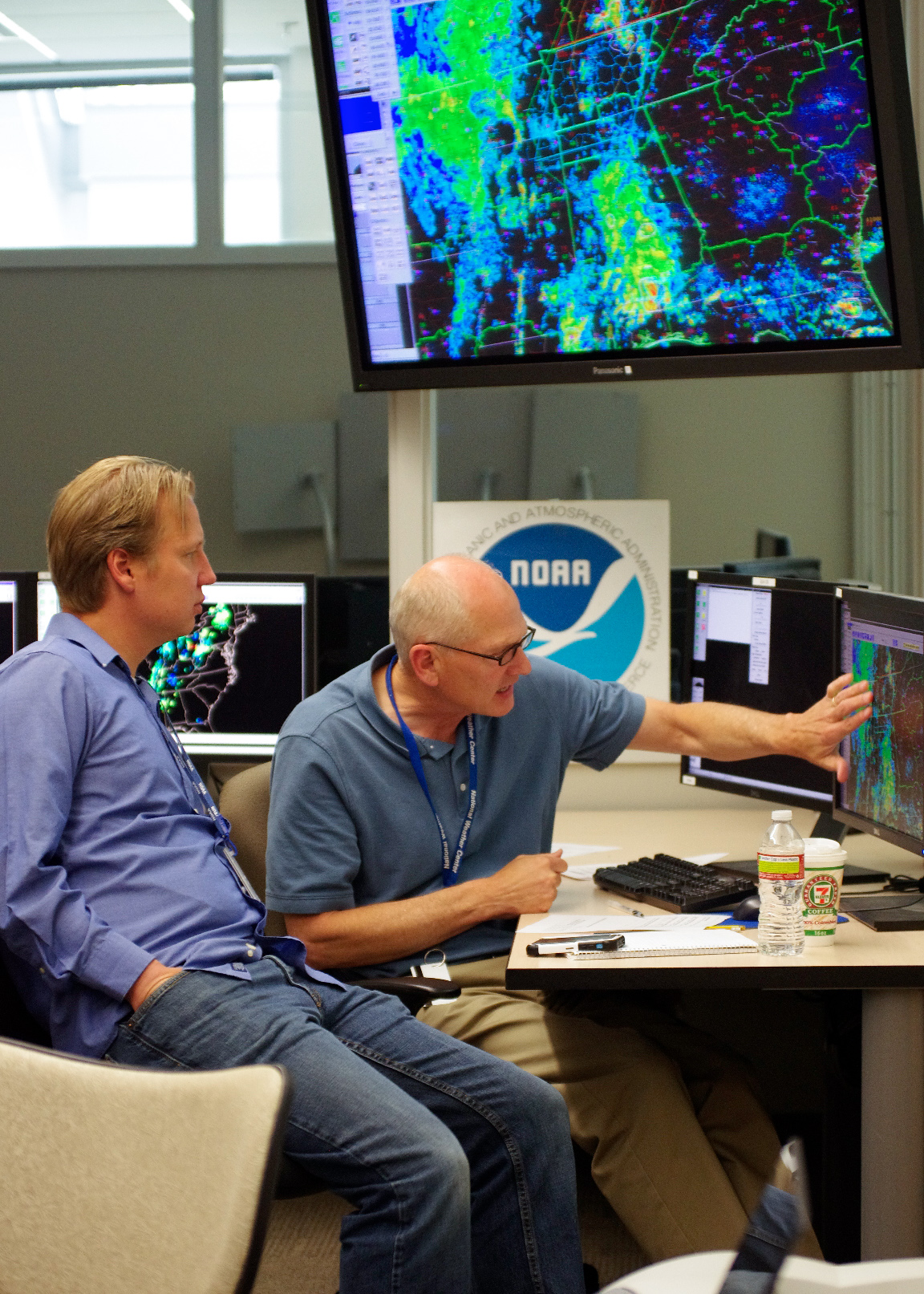

Connecting researchers and forecasters

“When you have a researcher that doesn’t know what it’s like to forecast and you can put them in front of a screen and say, ‘By this time we have to issue this outlook. How are we going to do this?’ it’s very different from anything that they are used to,” Clark said. “In research, you don’t have time constraints like that. It really gives researchers the perspective that they need to better gear their research toward helping forecasters.”

"By this time we have to issue this outlook. How are we going to do this?"

Forecasters who attend learn about the latest tools they may rely on in the next five to ten years.

Participants spend one week in the experiment, which allows five groups of researchers and forecasters to participate each year. The National Weather Service invites the forecasters and Clark helps select researchers to invite based on previous collaborations or affiliations with the tools that will be tested.

Clark was a doctoral student when he was first connected to the testbed experiments through his advisor, Bill Gallus, a professor of geological and atmospheric sciences at Iowa State. Gallus was one of the first university professors invited to the testbed.

“My first visit was in 2001,” Gallus said. “The invitation was based on the fact that I was one of the first university researchers really focusing on improving forecasting of thunderstorms. I have participated almost every May since that time.”

In 2007 the testbed was going to use a dataset that Clark needed for his dissertation. Gallus, his major professor at the time, helped Clark make connections and get access to the dataset. In 2009, as he finished his Ph.D., Clark attended the experiment for the first time.

Clark started in a postdoc position at the NSSL, and was able to step in when the testbed administrators found themselves short-handed.

Innovative tools can save lives

As a leader in the experiment, Clark helps choose tools that will be tested. These tools primarily are new weather forecast models - computer programs that analyze past and current weather data. Those that work well eventually get implemented into the forecasting field.

“The ultimate goal of the experiment is accelerating the transition of research tools into operations,” Clark said.

An important weather forecasting tool to come out of the testbed is a “convection-allowing model” (CAM), a type of model which depicts storms in higher resolution than previously was possible. First utilized in the testbed, it was implemented by the National Weather Service in the early 2010s.

“The ultimate goal of the experiment is accelerating the transition of research tools into operations.”

CAM models proved their value on May 19, 2013, when it was clear that conditions were coming together for possible severe weather and tornadoes in the Norman, Okla. area. While the old forecasting system at the time predicted a strong “cap,” or warm layer of air just above the surface, would inhibit storms from forming, Clark and the other testbed researchers were evaluating a new CAM model that predicted the cap would be broken by two supercells near Oklahoma City.

Several testbed forecasters and researchers shared the image of the experimental forecast on social media. One well-known researcher commented that the forecasts should not be taken literally because they can still have large errors.

“While this researcher was correct, on this day the storms simulated by the [CAM-based forecast] lined up almost exactly with the tracks of two observed supercells that tracked across Edmond and Norman producing damaging hail and tornadoes,” Clark said.

The CAMs give forecasters more detailed information for day-before forecasts than the previous forecasting models. Instead of a simple “expect severe storms tomorrow afternoon,” they allow forecasters to give more detailed predictions such as “expect isolated storms with large hail and tornadoes between 3 and 6 p.m. tomorrow.”

Expanding a legacy of learning

At the testbed, everyone is a student, learning from each other and generating data that Clark and his fellow researchers study much of the rest of the year. But Clark also ensures that graduate students are involved, whether through access to the data or attending the testbed.

"You have such a bigger impact on the field if you involve students."

“I have had several students contact him over the years for answers to questions, or to be pointed toward some of the datasets that are stored after the spring experiments end,” Gallus said, noting several former Iowa State students now have research positions in Norman.

Clark also mentors students through his appointment as an adjunct assistant professor for the University of Oklahoma.

His motivation to introduce students to research comes from his own experience at Iowa State, where he discovered his love for research through his required senior meteorology research project.

“Without that I don’t think I would have ever gotten a taste of what doing research is like,” Clark said. “I never would have known that I’m good at it and that I would want to do it for the rest of my career.”

Clark’s mentoring philosophy is modeled on what he learned at Iowa State, from his own experience working with Gallus: getting students involved, giving them ownership of their own projects and helping them make connections to others in the field.

“You have such a bigger impact on the field if you involve students because they’re going to grow in their careers, they’re going to have their own students and so your impact is so much larger,” Clark said.

From weather modeling to role modeling, Clark’s passion for innovation is clear. Whether it's a better understanding of the storms in the sky or leading students to research success, Clark’s leadership at the testbed improves many future forecasts.

Editor's note: Have you ever wondered why it's so difficult to predict the weather? We asked Clark to explain.