Aili Mu had just arrived at Iowa State in 2001 when her husband visited from Hong Kong. He brought along a few anthologies of Chinese short-short stories, a major literary craze at the time.

She read one and was instantly hooked. Short-shorts are like a cup of tea — quick to drink but richly steeped. They can be as short as a single page, and you can read one in minutes. Yet the small form creates space for life’s biggest questions.

“I remember I read a story over lunch, a story over breakfast, any little time you can. It brings you the satisfaction of an entire story with depth and dramatic plot.”

Mu, associate professor of world languages and cultures, became a world expert on Chinese short-shorts by accident. But her love for Iowa State students led her to turn them into a first of its kind, award-winning curriculum.

Local voices, global thinkers

What makes up a short-short? Chinese writers are always debating, Mu said.

"Some insist on the details," she said. "Some say it has to be the surprise ending. The magic of the genre is in the unscripted variety. For me, the capacity is all-embracing. Yet there is a form. Whichever way you maneuver, there is a form that enables you to give expression to what is in your heart."

The genre boomed for two decades before Mu began researching it. You can hear the excitement still echoing in her voice. She is most intrigued by grassroots short-short writers, from village school teachers to police officers, and what compels them to write in every county in China.

"The magic of the genre is in the unscripted variety. Whichever way you maneuver, there is a form that enables you to give expression to what is in your heart."

She once spent a day in rural China with a man who farmed his paddy field to feed his family and wrote short-shorts to feed his soul.

"He showed me where many of his stories conceptualized at his water lock. He sold a silo of grain to get his first computer. When I visited him, he had enshrined that now-defunct, old computer on a desk in his living room."

Many grassroots writers, though not isolated from China's rapid modernization, have stayed connected to their land, home life and traditional values, Mu said, much like an Iowa farmer. It's why their local voices are just right for helping Iowa State students become global thinkers.

"They bring the traditional way of thinking, the formative Chinese thoughts that could help even contemporary business behavior."

"I want to do the best for ISU students"

Mu's classes draw students from all across campus, including engineering and design students, some of whom have already made multiple trips to China.

“They are more in contact with other cultures every day,” she said emphatically. And it’s not enough, she said, to just introduce students to Spring Festival or dumpling recipes.

“I want to do the best for ISU students," Mu said.

Short-shorts are a pragmatic and powerful teaching tool. They can be quickly covered in class, yet give students insight into thousands of years of cultural tradition. For example, in a short-short titled “Skull- Shave,” a young boy faces his fear of a village ritual—a head shaving given with the quick strokes of a blade.

“My students thought this was an authoritarian kind of growing up, abusing a scared child,” she said. “They are culturally positioned to have this kind of reaction.”

The story helped her American students move out of their own familiar context and consider a Chinese perspective on ritual and respectful conduct, a key Confucian concept called li.

"You have to keep innovating"

When Mu first started blending cultural and language learning in her classroom, no appropriate materials existed. So, she wrote her own.

“The very important thing for any educator to realize is nothing stays put,” Mu said. “You can’t teach the old-fashioned way. You have to keep innovating. I feel like the students are taking me along. They have this need I have to meet.”

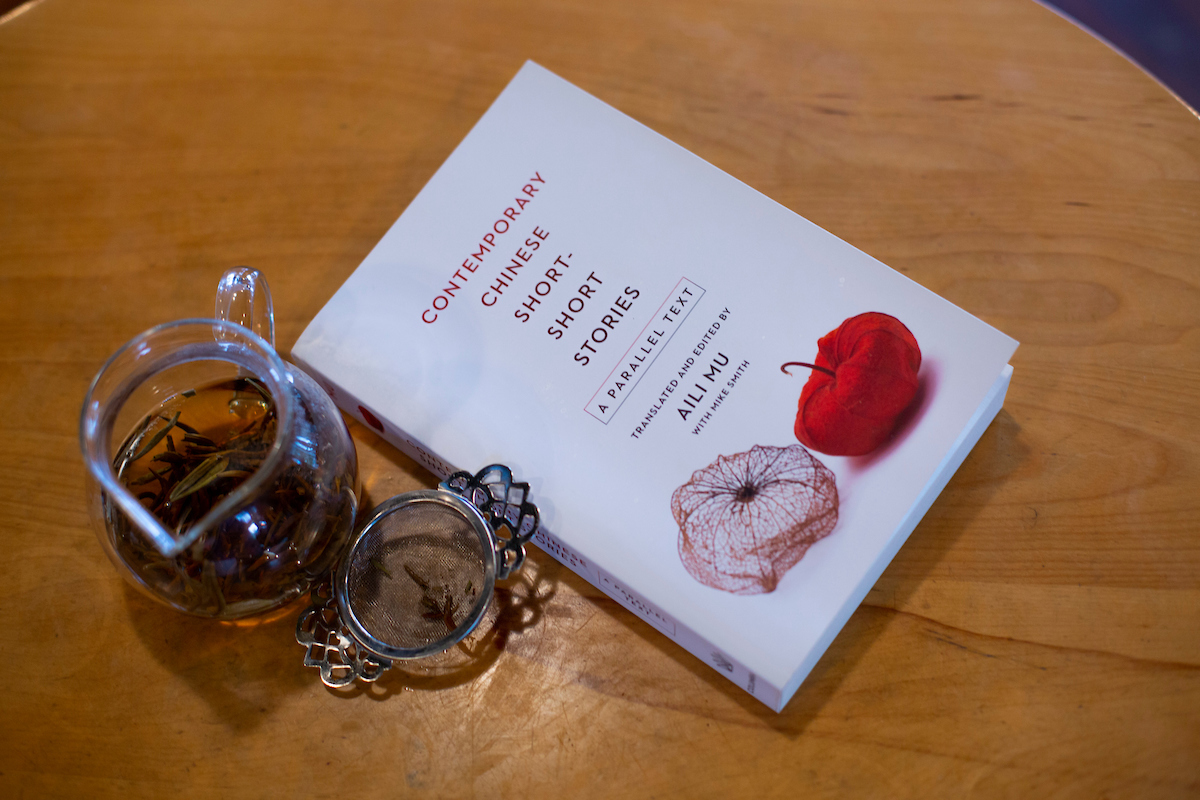

Mu had already co-edited “Loud Sparrows,” the first book to introduce Chinese short-shorts to the English reader. Then in 2017, Columbia University Press published her book “Contemporary Chinese Short-Short Stories: A Parallel Text.” The left side of each page is in Chinese, the right side in English. Each story is followed by Chinese vocabulary and discussion questions that are specific to the story.

"The very important thing for any educator to realize is nothing stays put. You have to keep innovating."

Many of those questions, perfect for class discussion, came straight from her Iowa State students.

“It’s a job that nobody in China could do,” she said of their questions. “It’s a job that no narrowly focused language instruction can do.”

Mu wrote the book for Iowa State students, not experts. But experts noticed anyway.

In 2018, she received the Association for Asian Studies’ Franklin R. Buchanan Prize for Curricular Materials, the only time the prestigious international award has honored a text combining education, language and culture.

“It wasn’t part of the plan,” Mu said, laughing.

The shared space between cultures

Her plan, after all, is to inspire students to keep moving into the shared space between cultures — the human space.

Lea Johannsen (history '15, M.A. applied linguistics '17) fell in love with Chinese culture and language at Iowa State and spent a summer helping digitize the short-shorts that ultimately ended up in Mu’s book. Mu’s classes fascinated her, she said.

In one class, Mu uses Chinese-to-English translation group projects to teach native and non-native speakers of Chinese in the same classroom at the same time. Students pair up and their grades are tied together for the semester.

Johannsen and her Chinese partner bonded over pop culture and video games. Her family hosted him in her parents’ Ames home.

“He said that to have us open our home to him and bring him into that authentic cultural experience was really meaningful to him. A lot of international students talk about that inability to break through and make meaningful connections. The class was great for fostering those connections.”

Mu’s innovative approach makes her the consummate teacher-scholar, according to Chad Gasta, professor and chair of the Department of World Languages and Cultures.

“Dr. Mu formulated an entirely new way of teaching Chinese language, literature and culture,” he said. “Both groups not only improved their cultural understanding and Chinese language proficiency—which is obviously so important to working in the global marketplace—but the arrangement also helped both groups discover a cohort that they may not have had otherwise. Her research and teaching have been groundbreaking for well over a decade.”

Learning is life

Mu’s own academic roots may surprise you. As a university student in China in the late 1970s, she studied English language and literature.

“China had just started to reform,” she said. “It was a time that people were very sincerely learning from the West.”

"Learning is not just to learn a vocation to survive. The more important part of learning is learning to be human."

Today, Mu easily inspires her own students to embrace language and cultural learning. Because for her, education is not a profession. It is life itself.

“I was brought up in a way that learning is not just to learn a vocation to survive. The more important part of learning is learning to be human. I feel very lucky to work at Iowa State. I love Iowa, treasure the opportunity to serve ISU students, and it makes me very happy to be part of their effort of cross-cultural learning.”