To Miriam Zach, music is instrumental to having a long, healthy life.

An Iowa native, Zach has traveled the world both performing and teaching others how to use music as medicine. Her career, though filled with variety, has always been linked to health.

“As a student at Northwestern University and the University of Chicago, I worked in clinics with adults and with hearing impaired and developmentally disabled children,” Zach said. “Then, in Germany, I taught piano to children with cerebral palsy, Down’s Syndrome and people with Alzheimer’s. The whole spectrum of life.”

For Zach, using music as medicine has no geographic or linguistic confines.

“It’s like the idea of Doctors Without Borders. It’s really independent of a political or economic boundary. It’s really international and independent of language,” Zach explained.

Zach joined the Iowa State University faculty in 2016 as the inaugural Charles and Mary Sukup Endowed Artist in Organ. The assistant adjunct professor teaches organ and harpsichord and leads an honors seminar that investigates a variety of topics related to music, including creating international health care, multilingual songs and ergonomic musical instrument design. Zach also researches the integration of music with healthcare.

In addition to her clinical work, she was the organist for the British Army of the Rhine and recorded in Princeton University Chapel for National Public Radio.

“I think I have lived many lives,” Zach said.

She not only has lived many lives, but also positively impacted the lives of others through her work and research centered around music and health.

An unexpected turn

Zach began to integrate music and medicine in 1994. Her life took an unexpected turn when her mother suffered a left hemisphere stroke that paralyzed the right side of her body.

The left hemisphere of the brain contains the centers for speech, language and logic. The stroke also caused aphasia, which is a loss of the ability to understand and/or express language. Language differs from speech, which is the physical ability to make sound.

“At the time, I didn’t know why. But when I sang to her, within a week after the stroke, her right hand started to move. And I said, ‘Okay, this is good. Something is working here. I have no idea why this works, but I know that it works.’”

As Zach’s mother was 80 years old at the time of her stroke, a full recovery did not seem promising. Zach recalled that while her mother was still in the hospital, singing changed everything.

“At the time, I didn’t know why. But when I sang to her, within a week after the stroke, her right hand started to move,” Zach recalled. “And I said, ‘Okay, this is good. Something is working here. I have no idea why this works, but I know that it works.’”

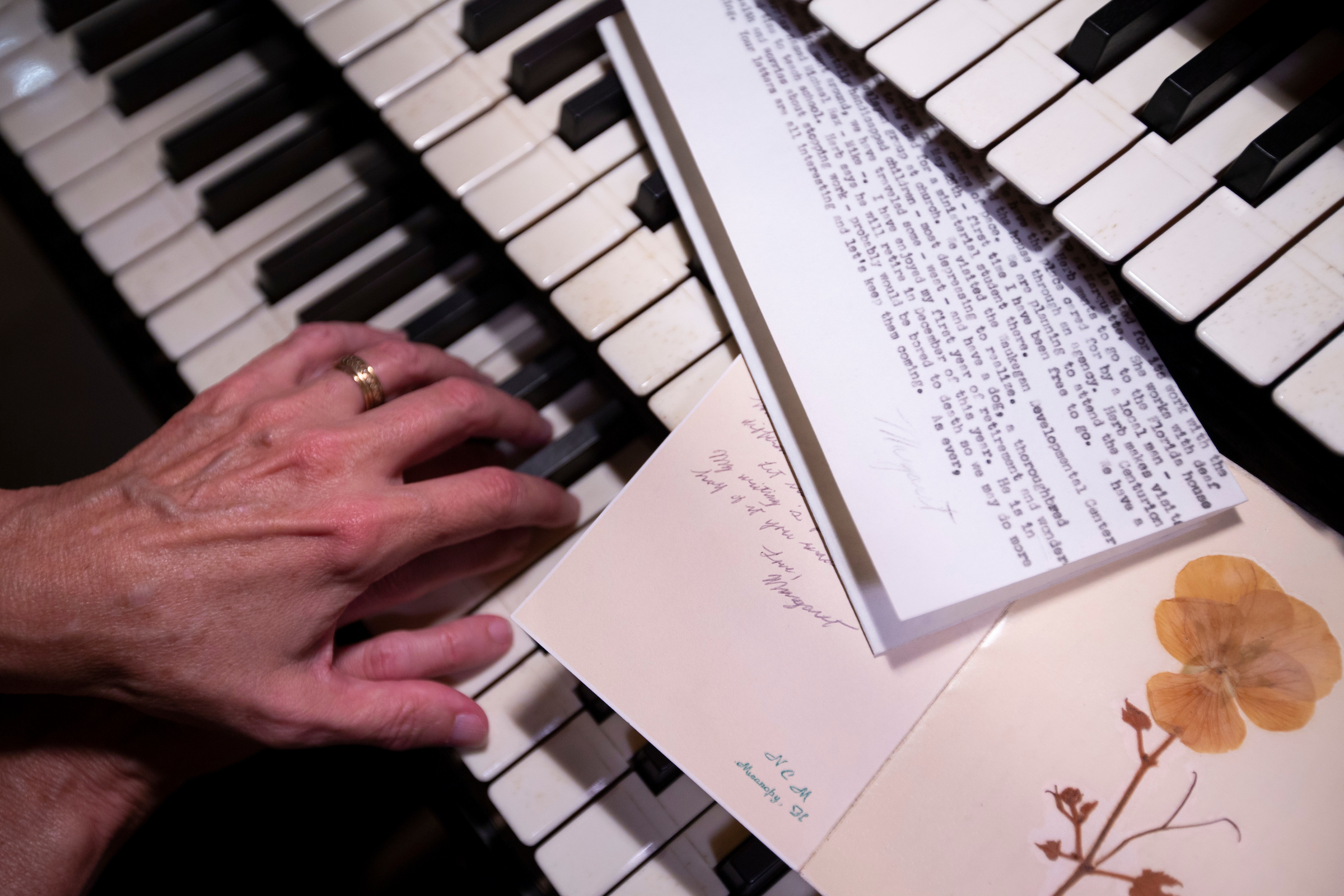

The song Zach sang to her mother that led to this incredible discovery? “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.” Over the next year, Zach worked with her mother at home - singing and teaching her to play the piano one key at a time.

“She had taught me piano, so I returned the favor,” Zach said.

Zach and her husband, Michael Muecke, associate professor of architecture at Iowa State, also created an ergonomic, acoustic environment to enhance mobility, safety, comfort and dignity. The idea was to surround her mother in sound so she could heal.

“It was like living in a piano,” Zach described.

Her mother regained some speech and her ability to walk, and even relearned how to sign her name.

Your brain on music

Zach learned that music is contained in both hemispheres of the brain, and using music allowed her mother to reroute her brain - and relearn functions lost.

“A stroke actually kills brain cells, and we had to re-route the pathways in her brain,” Zach said. “You have to call upon other areas of the brain to do the work of the damaged area. The other areas of the brain aren’t necessarily as good at some of the functions, but they can learn - and they did.”

“I work with sound, whether it is music or not, and learn how it helps people.”

Because Zach’s mother was a musician – a singer and pianist – before the stroke, her corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres of the brain, was highly developed.

The high level of development of the corpus callosum allowed for calling upon already-developed areas of the brain, making it easier to re-route and re-learn the lost functions.

Her mother’s recovery led to Zach’s research of the healing power of music and the desire to educate others.

Music for healing

“I work with sound, whether it is music or not, and learn how it helps people,” Zach said.

Zach is in the beginning stages of asking important questions regarding the effect of music on human biochemistry, specifically how music may be able to complement some pharmaceuticals.

“If the sound can be used instead of pharmaceuticals, which sometimes have negative side effects when combined, then you could still get results - such as pain relief,” Zach said.

The goal is to decrease the danger of mixing drugs that should not be used simultaneously, but still have a satisfactory result through the use of sound.

“I’m not saying no pharmaceuticals. I’m saying rely more on music and sound because it's not invasive,” she said.

Combining music and medicine has been powerful - and has inspired many of her students to do similar work all over the world.

An international impact

Since beginning her career as a professor by developing and teaching her first course integrating music and health at University of Florida in 2000, Zach has seen many of her students combine music and medicine into their careers.

“What's happening is they're singing and they're doing clinical research and shadowing physicians and then they're playing flute and singing - interweaving,” Zach said. “That's the next generation. That’s what has happened as a result of this research.”

One of Zach’s former honors students - who also happened to be a pre-medical student - joined the Peace Corps in post-Apartheid South Africa and worked with Zulu men who wrote songs to educate their own mothers and communities on AIDS prevention.

“There was the most remarkable video. The United Nations in New York picked up on his research and it went from there,” Zach said. “He went to South Africa to teach chemistry and then made this video with young men who were rapping and singing for their mothers as a Mother's Day offering. It brought tears to my eyes.”

Zach is proud of the reach of her work.

“It’s like these little ripples that have become waves, “she said. “And that’s where it started; I just wanted to help my mother.”