Maryl Johnson gave one of her first talks as a cardiology fellow in the 1980s on heart transplantation. The procedure was still experimental, and she read up on the research. All of it.

“Basically, I read the entirety of the world’s literature on heart transplant. It was a sum of about 100 papers,” she said. “Now you get that in a month or more.”

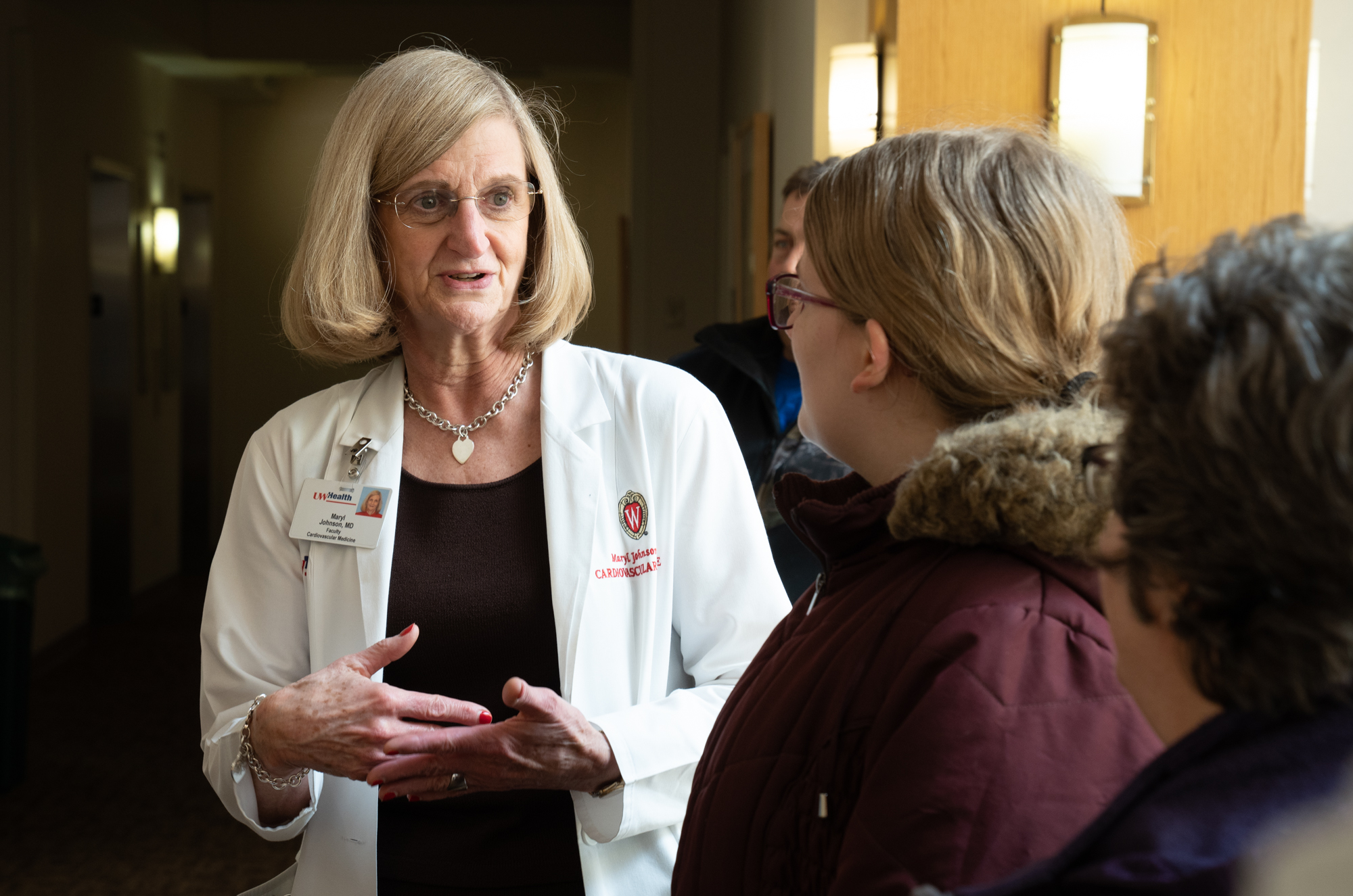

Johnson, a heart failure and transplant cardiologist and professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin’s School of Medicine, says she grew up with the field of transplant cardiology.

Or, in other words, she helped shape it.

An internationally recognized heart failure and transplant cardiologist, Johnson (’73 zoology) was involved with the first heart transplant at the University of Iowa. She is a Fellow of the American College of Cardiology, a past president of the American Society of Transplantation and the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation and the new president-elect of UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing)/OPTN (Organ Procurement and Transplant Network), which manages “the list” for over 114,000 people waiting for an organ transplant in the United States.

Not bad for an Iowa farm girl who never intended to become a doctor.

Finding her field

Johnson grew up on a farm near Fonda, graduating from Pocahontas Community High School with a class of 46 students. She came to Iowa State to study pre-med tech. Her heavy credit load her first quarter concerned her, and she went to talk to her advisor.

“She took one look at my folder that she had in front of her and said, ‘You don’t want to be a med tech.’ I said, ‘Oh, why do you say that?’ She said ‘You don’t really want to take orders from other people. You want to be instructing other people what to do.’”

The advice resonated. Johnson asked what she needed to take for Iowa State’s pre-med track, took her MCATs (Medical College Admission Test), was accepted to medical school at the University of Iowa, and never looked back.

“I don’t think that I had ever seriously considered becoming a doctor. But it certainly wasn’t something I was afraid of when it was brought to my attention that it might be a field I would love,” she said.

Johnson joined the growing ranks of women who entered medical school in the 1970s, a wave boosted by the women’s movement. Before leaving Iowa State, she blazed another trail, too. She joined the marching band her senior year, the first year women were allowed to participate.

“I don’t think that I had ever seriously considered becoming a doctor. But it certainly wasn’t something I was afraid of when it was brought to my attention that it might be a field I would love.”

Driven and dedicated

With transplant cardiology, Johnson entered an undefined but critically important field. The world’s first human heart transplant took place in 1967, only a decade before she graduated from medical school.

“I wanted to be in an area that was new and innovative and doing something different, but at the same time I liked having patients that I followed on a longitudinal basis," she said. "Having the longitudinal relationship, plus in a very sub-specialized area is something that has worked for me. I couldn’t have written a better script.”

Don Music of Iowa City was one of Johnson’s early patients.

In 1986, Music, then 31, collapsed at his construction job with what he thought was a bad case of the flu. Instead, he was diagnosed with end-state heart failure.

Heart transplant was an option, but an experimental one. Cyclosporine, an immunosuppression drug that can prevent rejection, had recently been tested in humans, creating a renaissance in transplantation.

“The survival rate was 50 percent at the time,” Music said. “I was also bed ridden and I knew I didn’t want to lay in the bed any longer. I didn’t have anything to lose by trying it. I think at the time most of the candidates were even younger than I was. None of us thought we would live very long with transplant, but we hoped it would help the science further down the road.”

He didn’t have much time to live. But he had plenty of confidence in a young cardiologist.

Johnson had recently helped establish the cardiac transplant program at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics. Her “small town Iowa” demeanor put Music at ease, he said.

“When you met her, you knew she was very intelligent and very compassionate,” he said. “She was just a farm girl, so down to earth. She didn’t really seem like a doctor, but she was very driven in making the program succeed. I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone as dedicated as Maryl.”

Music was only the 10th patient to have a heart transplant at the University of Iowa. He became close friends with other transplant patients of that era, but many have since passed away.

"I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone as dedicated as Maryl."

“I have to say that without the confidence I had in [Johnson] in the beginning, I’m not sure I would have the drive to make it through.”

An advancing field

Since those early days, Johnson’s own heart continues to beat for transplant. She built a career around running heart transplant and heart failure programs at university hospitals — first University of Iowa, then Loyola University, Rush University, Northwestern University and now University of Wisconsin, where she has been since 2002.

As the donor shortage became more apparent in the early years, the focus of her field shifted.

“We had to keep people alive until we could get a donor organ, and we got much more involved in heart failure,” she said. “Along that same time, there were a lot of studies coming out showing benefits of medicines for heart failure.”

“We do better with transplant because of the medication improvements. The whole field is continuing to advance like most fields of medicine, and I think that’s what has made it so exciting and yet very challenging.”

In the 1990s, Johnson started working with ventricular assist devices (VAD), a mechanical circulatory device implanted in a patient to help pump blood from the heart to the rest of the body. It can be a bridge to transplant or a therapy if transplant is not an option.

“The options we have to take care of heart failure are improving, medications are better than they were when I started in the field, the devices we have are better than when I started,” she said. “We do better with transplant because of the medications having improved. The whole field is continuing to advance like most fields of medicine, and I think that’s what has made it so exciting and yet very challenging.”

‘She’s really a gem’

When Walter Goodman first met Johnson, or “Dr. J” as he calls her, it was for a routine heart biopsy after his own VAD-to-transplant journey.

A professor of entomology at the University of Wisconsin, Goodman received a donor heart in 2013 from UW student Henry Mackaman. Mackaman, who died tragically from bacterial meningitis, saved several lives through his heroic generosity as an organ donor.

Heart biopsy looks for white blood cells in the heart muscle tissue, a sign of possible rejection. During the appointment, Goodman realized “Dr. J” was different than his many previous doctors.

“She spent a lot more time with me, and I started asking her questions and she gave me straight answers,” he said. “I realized I had found the person I was really interested in taking care of my healthcare. She’s really a gem. I didn’t realize at the time how much of a gem I’d gotten into.”

Goodman said a previous doctor had told him never to drink wine again.

“Her comment was, ‘We didn’t put you back together not to enjoy life. Go ahead and have a glass of wine if you want, but in moderation.’ That really endeared me to her,” he said.

In the years since, Johnson has generously shared her time with Goodman’s own pre-med undergraduates, giving a perspective on medicine beyond the “excitement you see on television,” he said.

“One of the things that came out in our discussions with the undergraduates is one of the reasons she got ahead is she volunteered for every nasty job that was available,” he said. “She decided she would work on holidays, when her male colleagues wanted the time off, and she said, ‘Okay, I’ll take it.’”

Now, instead of retiring to California as planned, Goodman and his wife may base their plans around the quality of healthcare he has received in the Midwest.

“I decided maybe we should become snowbirds, and part of that is because of people like Dr. J,” he said.

Gifts of the heart

In her role with UNOS/OPTN, Johnson is looking forward to helping shape the governance and policy of organ donation at a national level and making the best use of donor organs for their recipients.

“I love seeing my patients and interacting with my patients, but I also understand that the trailblazers have contributed by helping me get to where I am. Working with transplant related organizations is important to help other people have the opportunity to do what I did. We can’t do transplants without donor organs.”

Johnson has her orange dot on her Wisconsin driver’s license and has registered with her state organ donor registry.

“It changes the perception because if something tragic happens it wouldn’t be that the organ procurement team or donation team would need to talk to my family and ask them if they could take my organs," she said. "They would be able to go to my family and say, ‘Maryl indicated that she wanted to donate her organs. We’re here to help her give the gift that she wanted to give.'"

Gifts of the heart. They are Maryl Johnson’s specialty, in more ways than one.