A Cedar Rapids, Iowa, television station needs insights into Moms for Liberty’s weak performance in recent local elections. A South Carolina-based online political website is curious about Nikki Haley’s standing in Iowa. Washington Post political columnist E.J. Dionne wants to talk about recent polling.

Welcome to the life of an Iowa State political scientist during election season. More specifically, welcome to the life of David Peterson, who holds the Lucken Professorship in Political Science, which was established with a gift from Kent A. Lucken, a 1986 Iowa State graduate in political science, and his wife, Kristen Lucken.

Through his frequent media interviews, research and perhaps more significantly, his current polling work with students, Peterson plays a vital role in helping Iowans stay informed about electoral politics, and the country informed about what’s happening in Iowa.

“It’s important that we understand the world around us at a base level,” he said. “We need to be better informed about how the world actually works, and how and why politics works the way it does.”

While the Iowa caucuses have gone through significant scrutiny since the last general election, the state remains a player in national politics. This means that political scientists like Peterson are in demand as expert sources for print, broadcast, and online media. It’s a role Peterson likes … with some qualifications.

“Part of being a political scientist is the specialized knowledge and expertise on a topic that a lot of people care about,” he said. “It means we frequently get contacted by media outlets for our perspectives on the news. It is something I generally enjoy, but it comes and goes. Right now, I’m getting a lot of contacts because of the Iowa Caucuses, but after those are done, they will be much less frequent.”

Election research

Peterson’s research focuses primarily on elections, public opinions and voting behavior, with the goal of providing voters a deeper understanding of electoral politics beyond headlines and snarky social media posts.

For example, an ongoing research topic that has already produced a book and several research papers is voter mandates. Peterson’s work in this area has primarily focused on dispelling the idea that election victors, by virtue of winning, truly have mandates from voters.

“Elections are messy, and voters make decisions for a lot of different reasons. There is never really a clear policy message to be found in election results,” he said. “But to members of Congress, that doesn’t matter. They don’t have the luxury of taking the chance that there isn’t a message from voters in the election outcomes. As a result, members of Congress will act as if a mandate occurs even when there is no evidence of it. They change their votes on bills, with the party advantaged by the mandate becoming more emboldened and less moderate, and the party disadvantaged becoming more moderate.”

Mandates can arise when elections have consistency up and down the ballot.

“Winning the presidential election is necessary, but it isn’t enough,” he said. “Instead, it’s the down ballot races, elections for the House or governors that really matter.”

He also has done work that helps voters understand the behaviors of voters who don’t necessarily look like them. For example, he co-authored “Ignored Racism” with Mark Ramirez, a former graduate student of Peterson’s when he taught at Texas A&M. The well-received book provided new perspectives on how white voters’ attitudes toward Latinos shapes their political views.

Natalie Jones-Kerwin, a former Peterson student at Iowa State, investigated how American Indian identity shapes political behaviors. Her study was part of her successful admissions application to graduate school at the University of Wisconsin and was expanded into a Political Behavior journal article that will be co-published with Peterson.

Early interest

Peterson’s interest in American electoral politics began at a young age, and he suspects his Canadian mother had a lot to do with it. She married an American soldier, who died in an explosion on the USS Forrestal aircraft carrier during the Vietnam War. She then moved to Seattle to be near family and met her second husband, Peterson’s father. He was killed in an accident involving a drunk driver when Peterson was 3. His mother moved the family to Canada briefly, but she wanted her “kids to grow up in the United States. She talked a lot about the importance of the American identity, and part of that was paying attention to politics,” Peterson said.

He studied political science at Gustavas Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota, where, in 1992, he became fascinated by a brash billionaire populist named Ross Perot. A headline-dominating third-party candidate from Texas, Perot “seemed to come out of nowhere and had such a draw on voters,” Peterson said. “It struck me that in a lot of ways the Perot campaign was similar to (George) Wallace’s in the ways they both appealed to economically disaffected white voters.”

That observation inspired a paper he did for a campaigns and elections class taught by Chris Gilbert, a political science professor whom Peterson credits as a mentor. Impressed by Peterson’s work, Gilbert urged the undergraduate to further explore the dynamics of third-party candidates. Peterson acted on the advice and, in doing so, set himself on a path to a career as a deeply student-focused political scientist.

Working with Gilbert, Peterson analyzed voting data for Perot, Wallace, who ran as a third-party candidate in 1968, and John Anderson, who ran a third-party campaign in 1980. He found that the more religious the voter, the less likely they were to vote for a third-party candidate.

“Churches play a key role in politics, for both Republicans and Democrats, and there is an incentive to stay with major parties,” Peterson said.

This work led Peterson, Gilbert, and two colleagues to co-author a 1999 book titled, “Religious Institutions and Minor Parties in the United States.”

After this experience, “I was hooked and knew this was what I wanted to do,” Peterson said.

Students and polling

Peterson has received a lot of media interest — such as the call from Dionne at The Washington Post — regarding the ISU/Civiqs poll conducted by the Iowa State political science department.

Peterson took over the department’s longstanding polling project in 2019 and promptly made changes. He moved away from traditional random phone polling because it was “outrageously expensive,” and contracted with Civiqs, a firm which conducts online polling using pools of potential respondents.

Peterson notes that “students are cynical about politics, and with good reason, but they get that politics matter in their lives.”

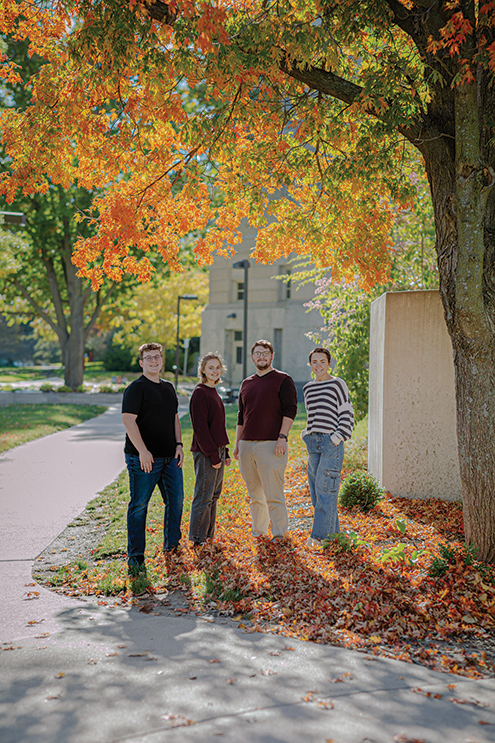

Understanding this, Peterson invited undergraduates to get involved with the 2024 polling project.

“I’ve been working with undergraduates for a long time. It’s always been part of what I do and it is the most fun part of what I do,” he said. “That kind of faculty-student mentorship changed my life. As a land-grant university we should be providing these opportunities to the extent we can for students who express an interest.”

Polling was conducted monthly from September 2023 through January 2024. The project surveyed and tracked evolving perspectives of more than 1,000 registered Republican voters leading up to the Iowa caucuses. Respondents to Iowa State polls included repeat respondents and new ones. This ability to measure the stability and fluctuations in Iowans’ perspectives was one of the project’s strengths, Peterson said.

Because of the complex nature of polling, Peterson’s students are getting “a high impact research experience,” he said. “They are looking beyond the horse race aspects of the Republican primary battle, and instead considering their own questions about the state’s political landscape and incorporating them into the polling project.”

“The polling project gave me a taste of how academic and political research takes place,” said Eleanor Chalstrom (’24 political science, journalism and mass communication). “I studied how my home state views its political surroundings and got to ask those questions firsthand. The study allowed me to familiarize myself with research methods and construction.”

Chalstrom’s survey questions examine voters’ emotional reactions to candidates. She found that many poll respondents still like Trump but are anxious about whether he can beat Biden. She noted the opportunity provided by Peterson has changed her view of politics and beyond.

“Political science is my secondary major. It was never a passion of mine. This project changed my mind about political science and research. The nuts and bolts of academic research are something that I greatly enjoy. Without participating in this study, I would never consider careers in the political world or continue in higher education,” Chalstrom said.

Dylan Miller (‘24 political science) is looking at why some people participate in the political process, while others don’t. For him, the polling project gives Iowans “an opportunity to see what the state around them looks like. When you live in a city, it’s easy to get a distorted view of the world around you, but this data that we’re producing gets right to the heart of the minds of voters in Iowa, even if we’re mostly focusing on Republicans this time around. If nothing else, everyone who digs into this data will be able to really ‘get to know’ your average Republican voter in Iowa.”

Making sense of politics

Students trying to understand the political landscape. Reporters pursuing immediate insights into election-year developments. In the middle of it all is Peterson, fielding questions, guiding curiosity, and seeking answers to his own inquiries, all with the goal of helping us more clearly realize the impact that politics has in our lives.