In the remote Republic of the Marshall Islands, a nation of islands and atolls that dot the central Pacific Ocean, Trudy Huskamp Peterson methodically hauled file boxes out of storerooms. Her mission: preserving the records of the Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal.

“There is no way we can preserve those records on the island where they now exist - it is in grave danger of enhanced flooding, tropical storms and land being washed away,” Peterson said. “The island averages only seven feet above sea level.”

Until recently, adapting to the digital age was one of the biggest problems facing archivists. Now, archivists like Peterson are confronting new challenges, like the effects of climate change on archives, and the need to create security — or backup — copies when archives are threatened by oppressive regimes or unstable governments.

Today, Peterson (’67 English, history), once the Acting Archivist of the United States, whizzes around the world rescuing records at risk. With considerable pluck and cool proficiency, she has worked to preserve records of human rights and of truth commissions in South Africa and Honduras. She has consulted with the Special Court for Sierra Leone, among many other institutions, and spent three years working with the police archives in Guatemala.

“All these things happened among us”

Peterson fell in love with archives by accident. She grew up in what remains her favorite place, the northwest Iowa farm that her great-grandparents settled. She chose Iowa State University for its reputation as academically difficult. Teaching history sounded mind-numbing to her, but working with its raw materials was a dream.

“‘All these things happened among us’ is one of my favorite sayings,” she said. “It comes from the El Salvador Truth Commission. Understanding how we got to where we are. What did people do? How did they choose to organize themselves? All of that I simply find fascinating.”

During her first archives job at the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum in West Branch, Iowa, Peterson discovered a fascination for reading "100-year-old gossip." She worked with archives and museum exhibits and grew deeply interested in documents, such as letters from U.S. farm organizations describing the depth of despair during the Great Depression.

“‘All these things happened among us’ is one of my favorite sayings. It comes from the El Salvador Truth Commission. Understanding how we got to where we are. What did people do? How did they choose to organize themselves? All of that I simply find fascinating.”

After earning her master’s and Ph.D. in U.S. history at the University of Iowa, Peterson began a decades-long career with the National Archives. In 1993, she was the first woman to be appointed Acting Archivist of the United States.

Records of our national life

Archivists use two powers to ensure that a record of the past is maintained for the future, Peterson said.

“The first power is to decide what to save and what to throw away,” she said. “The second power is to tell you what you’ve got. What we did save.”

As the nation’s record keeper, the National Archives holds millions of federal documents, manages 14 U.S. presidential libraries and includes a network of research facilities and federal records centers across the country. But its most vital mission, Peterson said, is selecting and preserving the records of national life today, including yours.

“There is no part of the life of people in a country that isn't touched one way or another by archives,” Peterson said. “Was your father in the Vietnam War? Those records would be in the National Archives. Do you get a government pension? Those records would be there. We are vital to the health of the nation, not just because we hold the records of Supreme Court decisions or District Court decisions or because we save the records of wars and of peace settlements, but on a personal level.”

“There is no part of the life of people in a country that isn't touched one way or another by archives."

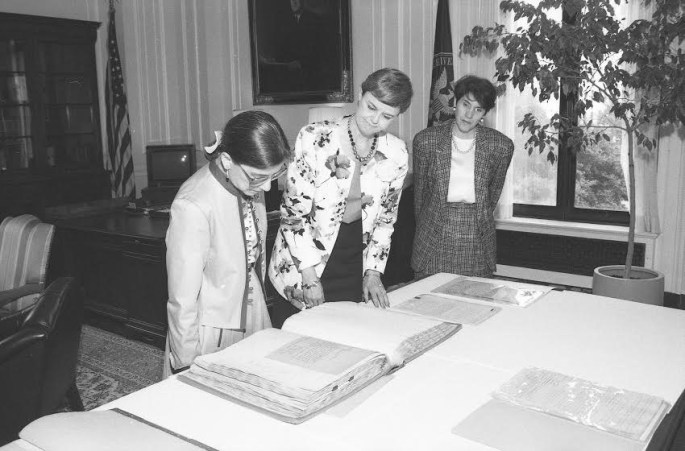

Those records can range from the naturalization record of your great-grandmother to groundbreaking constitutional amendments. Once after Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was sworn in to the U.S. Supreme Court, the justice wanted to see the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote, Peterson said.

“She came down to the archives, and we got out the big bound volume of all the ratifications of the amendment,” Peterson said. “That was fun. You have this feeling when you look at it of saying, ‘Yes, yes, it’s done.’”

A nose for archives in need

During her years at National Archives, Peterson filed away experiences with archives and human rights, from working with Bureau of Indian Affairs records to serving on the U.S. – Russia MIA/POW Commission that worked to bring closure to families of missing service members.

She also developed a nose for archives in need. When she retired from the National Archives in 1995, she read that the records of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, a vast treasure trove for Cold War research, had been obtained by George Soros' Open Society Institute in Budapest, Hungary.

What they need to acquire next, Peterson thought, was an archivist.

“I said to my husband, 'Shall I write and tell them that, offer my services, give them some advice?'” Peterson recalled. “He says, 'What have you got to lose except a stamp?' So, I wrote them a letter, put a stamp on it. I got a phone call, they invited me to come to New York and talk to them and got hired.'”

She was hired as founding executive director for the Open Society Archives (OSA), an institution that now holds Cold War research materials, along with a sizeable collection of underground literature and records related to international human rights violations and war crimes.

During Peterson’s time with OSA in Hungary, she also devised strategies to gather records documenting the war happening nearby in the former Yugoslavia.

“I had the idea that what was being broadcast at night on television in Croatia, Bosnia, and in Serbia was different than what we were seeing internationally, and they were probably telling the story differently about the same incident,” she said. “We hired people in those three countries for a period of a couple years to copy the nightly news so that somebody could sit in Budapest and look at it and say, 'Now I want to look at the invasion of Kosovo and what are they saying in each of the three localities about the invasion of Kosovo.’”

By 1999, Peterson had found her next archives in need. She accepted a position as the director of archives and records management with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The archives were new, and no one had yet thought about them in historical terms or organized them for public use, Peterson said. One of her main objectives was fast-tracking the creation of a true archival program in time for UHNCR’s upcoming 50th anniversary.

“It’s currently running really well and I’m very pleased that it is operating as well as it does,” Peterson said.

When Peterson and her husband settled back in the United States in 2002, she established her own part-time archival consulting company that quickly grew into a full-time job answering calls for help from archives around the world.

“People always think I’m brave, but I’m not that brave honestly,” Peterson said, laughing. “I respond to phone calls. What can I say?”

Facing history

Often, when history is tough to face, it is even more important to preserve.

The United States exploded 67 atomic bombs in the Marshall Islands from 1946 to 1958, a series of nuclear tests which vaporized entire islands and stripped generations of their homes, livelihoods and health. When the Marshall Islands gained independence in 1986, the agreement required the U.S. to provide $150 million for a tribunal to settle claims ranging from thyroid cancer to miscarriage to the destruction of fishing stock.

“It’s a mix of very serious medical records, which I believe had historical importance, because this was an eradiated population that was followed for years and we have the medical records of the claimants,” Peterson said. “But, also because it is one of the United States’ original sins. We blew up people’s homes and we did it knowingly.”

In 2012, Peterson made the first of several trips to Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands, to help assess the tribunal records for preservation. As rising sea levels caused by climate change eat away at the low-lying Marshall Islands, the records are increasingly vulnerable.

“Climate change is a big deal, and I keep going around the world trying to talk about it. I am convinced we have to face it and look at repositories of archives, but also active places."

In partnership with international collaborators, Peterson selected records from the Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal that she believed held permanent value. Digitized copies were then transferred to organizations in Switzerland and Spain for safekeeping. With limited international funding for the project, Peterson had to provide both brains and brawn – but the tedious work of scanning, stacking and packing decades of files didn’t faze the world expert a bit.

“I loved it,” she said. “I think this is really important, and I like doing it.”

The Marshallese, once displaced by those nuclear tests, now face a second displacement by climate change, as do archives everywhere, Peterson said.

“Climate change is a big deal, and I keep going around the world trying to talk about it with groups like UNESCO and archival groups,” Peterson said. “I am convinced we have to face it and look at repositories of archives, but also active places. Churches hold records. Businesses hold records. Are they in flood zones? Is Sioux City going to be flooded, and if so, where are the records of business in Sioux City? Where are the records of the various churches? Where are the records of the museum? We know this is going to happen and climate change is affecting us.”

Violators of human rights

Picturing files in floodwaters is one worry that keeps Peterson up at night. The need for safe havens for archives in danger is another. The raiding of human rights organizations’ offices — computers stolen, buildings burned and files smashed — happens far too often, she said.

“I worry very much about people in various locations around the world, where they are sitting with this extremely important material that documents human rights violations and they are at risk,” Peterson said. “They need to get a security copy somewhere else.”

Last fall the International Council on Archives, an international non-governmental organization founded in 1948, adopted a position statement on safe havens for archives in danger. Peterson and other archivists drafted the document as part of an effort led by the foreign ministry of Switzerland.

“We are working now through the details,” she said. “If you’re worried that the records you have are in danger and you need to get them into a third country and you need to get them into a third institution, how do you go about that?”

For example, in 2005, a massive archive of records was uncovered in Guatemala, including records detailing human rights abuses by the former Guatemala National Police during the country’s 36-year civil war. Peterson traveled back and forth from Washington, D.C. to Guatemala for three years, training local staff on how to arrange and describe the records for archival research. A security copy of significant records now sits in Switzerland, Peterson said, which protects the information and preserves it as a resource for justice.

“Guatemala is in a political crisis right now,” she said. “Much of the democratic progress that enabled us to do things with the police archives and use them to hold perpetrators accountable is flying backwards.”

Preserving history, protecting rights

Peterson, once dubbed the “globetrotting gonzo archivist extraordinaire” by Harvard historian Kirsten Weld, is a prolific writer and speaker. Peterson wrote the book “Final Acts: A Guide to Preserving the Records of Truth Commissions,” as well as many other publications, and in recent years she has led seminars and workshops in Istanbul, Bangladesh, Ukraine, Colombia, the Philippines, Lebanon and Tunisia.

"Access to archives empowers people. We have to be able to preserve and maintain those materials that provide our history, help us understand who we are and how we got to this place and in a very personal way protect our rights."

Last year Peterson also found time to write what she considers one of her greatest contributions to her field. In honor of the 70th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Peterson penned a series of essays on each of its 30 articles and their intersection with archives.

“Access to archives empowers people,” Peterson said. “That means we've got to identify the records that are created. We’ve got to preserve them, and we've got to make them available wisely. We have to be able to preserve and maintain those materials that provide our history, help us understand who we are and how we got to this place and in a very personal way protect our rights.”