Jody Ewing, a former journalist, knows the value of a good question.

As the founder of Iowa Cold Cases and a licensed private investigator, she also knows good questions sometimes have dangerous answers.

“You ask the wrong person the wrong question, and you end up dead.”

The families who never forgot

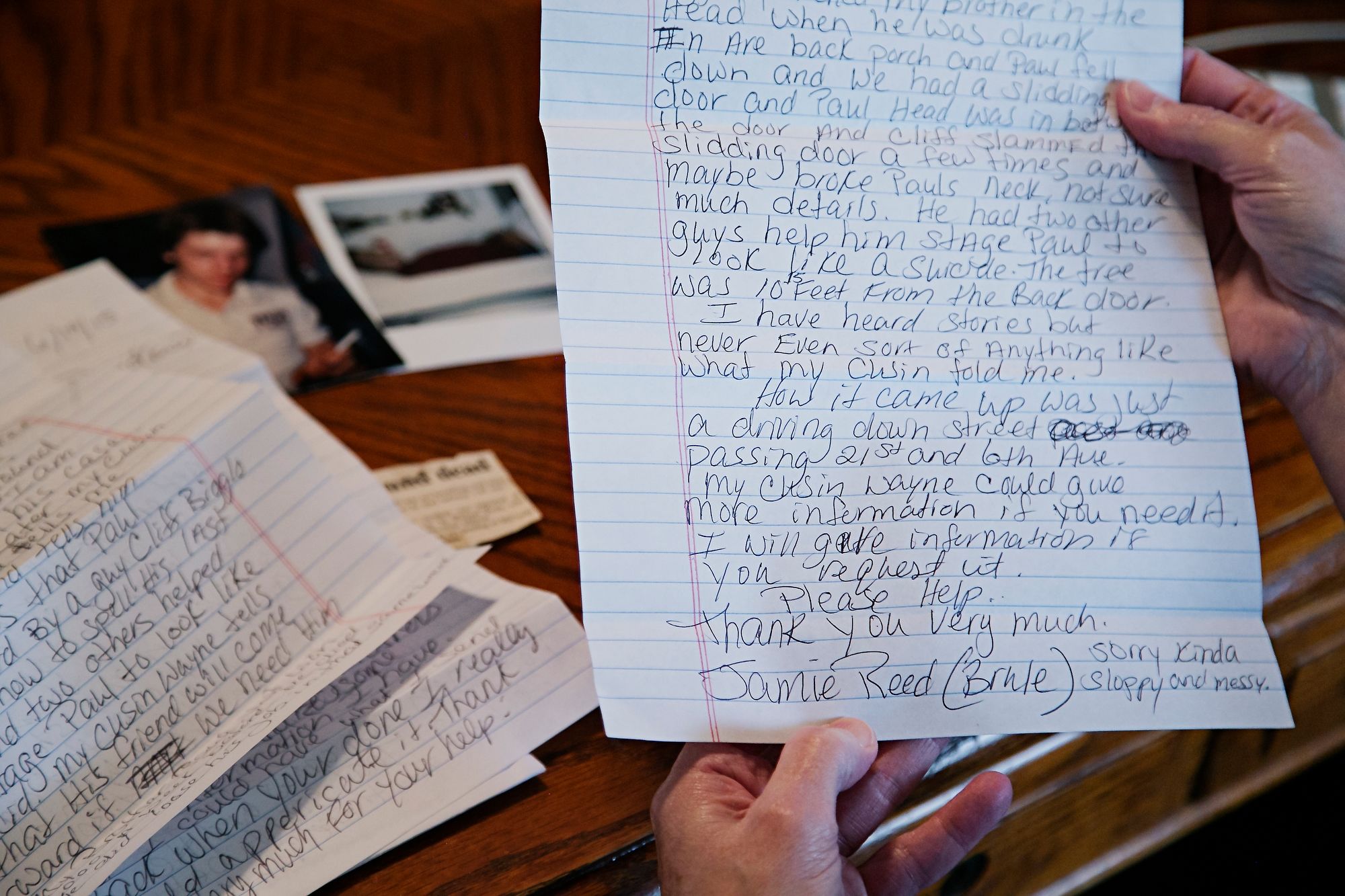

In May of 2004, Ewing (‘08 liberal studies) wrote a story for the Sioux City Weekender that changed her life forever. Her feature on an unsolved 1974 triple homicide, the first of a six-part series on cold cases, received a profound reader response.

“I got so many phone calls and emails where people were saying, ‘I live close to Sioux City. My dad was killed here or there.’ I could sense this desperation in their voices, and it was like they had no one. These were murders that happened 30 or 40 years ago, but everyone’s forgotten about it. There’s been nothing written in the paper about it for the last 30 years. They were so passionate about it. It still affected them that deeply years later that their loved one’s murder was not solved.”

"I could sense this desperation in their voices, and it was like they had no one."

That deluge of pent-up pain prompted Ewing to rewrite her own life story.

She did what seemed easy at the time for a journalist. She told families she would check if police had anything new on their loved one’s case and considered making a simple website.

“I started out thinking, ‘I’m just going to get ahold of the counties and major cities and ask them to send me a list of cold cases. I’ll create a website and it will list all the unsolved cases in Iowa, and if I know more I can add that, but it will mainly be a list of names and cases.’”

She paused.

“I thought this whole thing would take a year.”

Iowa Cold Cases

Fourteen years later, Ewing’s nonprofit Iowa Cold Cases averages around 100,000 unique web visitors per month. Searchable by year, decade, city, county and victim name, it is the first public statewide website of unsolved murders in Iowa and in the nation, Ewing said, with more than 550 cold case summaries.

Ewing said people have always been intrigued by unsolved crimes, whether the case happened last year or 100 years ago. Her site lists cases dating back as far as 1847.

The importance of justice, she said, is one reason people still visit Villisca, Iowa, to see the house where eight people were murdered in their sleep with an ax in 1912.

“We, as human beings, have an innate sense that others must be punished or held accountable for having committed such heinous acts of violence,” Ewing reflected. “We want to know how an especially brutal crime could have occurred here in rural America. We want to know why it happened and what circumstances allowed the offender to avoid detection.”

A connection to people without answers

Publishing a cold case website is not a slow news affair. Ewing’s work keeps her scrambling all day long.

“Every day is different, but it’s the same in that it’s hectic every day. It’s from the moment I wake up until 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 in the morning.”

She regularly wakes up to a 7:00 a.m. call or text from a victim’s relative eager to connect. The rest of the day is a constant ping of more calls, texts, emails, Facebook messages and reader comments. Ewing updates an average of ten different victim case summaries a day, linking media reports, adding new information from families or posting updates from court decisions.

“Right now, there are about a dozen cases sent by law enforcement where I need to review what was sent, read through the articles they included and then speak myself with the victim’s family members.”

Cold cases are not frozen. They are fluid. To keep up, you need a solid grasp of the details.

“I remember well what Capt. Lisa Claeys of the Sioux City Police Department told me when I first began writing the cold cases for the Weekender,” Ewing said. “She said that a cold case file isn’t something an officer or investigator can just glance through every now and then, but that they must read through the file and become intimately familiar with the names, details and information it contains.”

In some cases, Ewing now knows the facts as well as her own family tree.

“I started having a real connection to these people who did not have answers,” she said.

Evidence of a liberal arts degree

Ewing makes those connections easily, in part because of her liberal arts and communications background. A non-traditional student, Ewing finished her bachelor of liberal studies degree online at Iowa State.

It turns out an LAS degree really does help you learn to communicate effectively—in Ewing’s case, she can rotate between talking with a police detective and texting with a distraught relative and never miss a beat.

“All my coursework – which focused on communications, social sciences and criminal justice – has ended up playing a role in the work I do every single day."

The unfortunate reality is people are sometimes scared to talk to law enforcement, Ewing said. Her ability to build trust and rapport with families can help fill a gap.

“All my coursework – which focused on communications, social sciences and criminal justice – has ended up playing a role in the work I do every single day,” she said. “My coursework in communications has taught me to be able to hold a very constructive conversation with almost anyone.”

From the details of each case summary, a life arises. Holly Durben loved animals and once nursed an injured deer back to health. Susan Kersten was a talented visual artist.

“I try to tell each person’s story in a way where readers feel as if they can relate to the victim,” Ewing said. “When readers come to care about an individual they’ve never known, they tend to take a greater interest in seeing the case solved.”

A voice for the victims

“Dana, they made an arrest.”

On April 20, 2016, five years after Tony Ray Canfield was murdered during a Sioux City home invasion, his widow Dana Canfield received a call that police had made an arrest. Ewing was one of the first people she contacted to share the good news.

As a surviving spouse, Canfield endured grief, guilt and the burden of rumors and hurtful assumptions about her husband’s death. Iowa Cold Cases was her lifeline.

“I didn’t have anyone else,” Canfield said. “That’s all I had. Jody gave me a way to still fight for [Tony] and to keep his memory alive. I’ve told Jody, ‘You’ve never judged me. You just wrote the story. You’re my hero.’”

Through Iowa Cold Cases, Canfield found support and friendship. Every Thursday, she and other victims’ relatives would share each other’s cases on Facebook with links to Ewing’s summaries.

“Those articles are so powerful,” Canfield said. “Whether it’s twenty years later or 100 years later, it’s still a voice for victims who never got justice.”

When cold cases get solved

“Solving any case, particularly the ones decades old, involves an extensive ensemble,” Ewing said, which includes law enforcement, attorneys, private investigators, victims’ relatives and witnesses.

While she is reluctant to give Iowa Cold Cases credit for a solved case, sometimes its work clearly helps pull the pieces together.

In 2005, the body of an unidentified man was found floating in the Des Moines River near the Center Street Dam in Des Moines.

Five years later, WHO-TV Channel 13 in Des Moines aired a story on “John Doe 2005” for its “Cold Case Thursdays” segment. The former series, led by reporter Aaron Brilbeck, helped put cases from Ewing’s website in the public eye.

The story of John Doe 2005’s identification has its own twists and turns, but through their partnership and the work of the Polk County Chief Medical Examiner, the body of Robert Bryan McMahon was eventually positively identified.

Ewing said it is a delicate balance to be optimistic in cold cases while not raising false hope for families.

“Too many times, I’ve heard family members say, ‘They’ll never make an arrest. I gave up all hope several years ago,’ when the primary suspect is known to police and still very much alive,” she said. “As any law enforcement official would tell you, investigators know in most cases who committed the crime but knowing who did it and proving it in a court of law are two very different things.”

The last chapter

As Iowa Cold Cases gained attention and media inquiries became more frequent, Ewing fielded the same question again and again: “Do you have a family member who was part of a cold case?”

Her answer was always “No.” Until August 28, 2007.

That day, two years after Ewing started the website, her stepfather Earl Thelander was injured in an explosion after thieves stripped copper from his farm’s propane and water lines and let propane gas fill the house. Thelander died four days later.

It never crossed her mind the case would grow cold.

“The weeks passed and turned into months and that first anniversary came around. Then at a deeper level I could understand the frustration that all of these people have with not getting answers to their own loved ones’ cases. And it doesn’t matter if the case is five years old or 50 years old. It’s like it happened yesterday.”

“You’re trying to get justice for family members. It just gets in your blood and it’s hard. There is really no off button. You just can’t forget about it and go to sleep at night knowing that.”

No law requires her to answer every late-night phone call or flip through case files at 2 a.m. But she does it anyway. Those families, she said, have committed their lives to finding answers for their loved one’s death. Ewing has, too.

“You’re trying to get justice for family members. It just gets in your blood and it’s hard. There is really no off button. You just can’t forget about it and go to sleep at night knowing that.”

Ewing is working on a memoir now about creating Iowa Cold Cases. She may try her hand at a crime novel in the future.

But for now, the stories she cares most about are the ones without an ending.

“All our lives are filled with stories, and every individual deserves to write his or her own endings. By giving voice to these silenced victims and ensuring their stories are told and kept alive until justice prevails, the possibility still exists to provide a fitting ending to the last chapter they had yet to tell.”