Imagine if we could live longer, better lives. Lifestyle choices play an undeniable role in how long we will live and how well we will age, but the molecular differences in our genes decide, at least partly, whether we will live to 60 or 100.

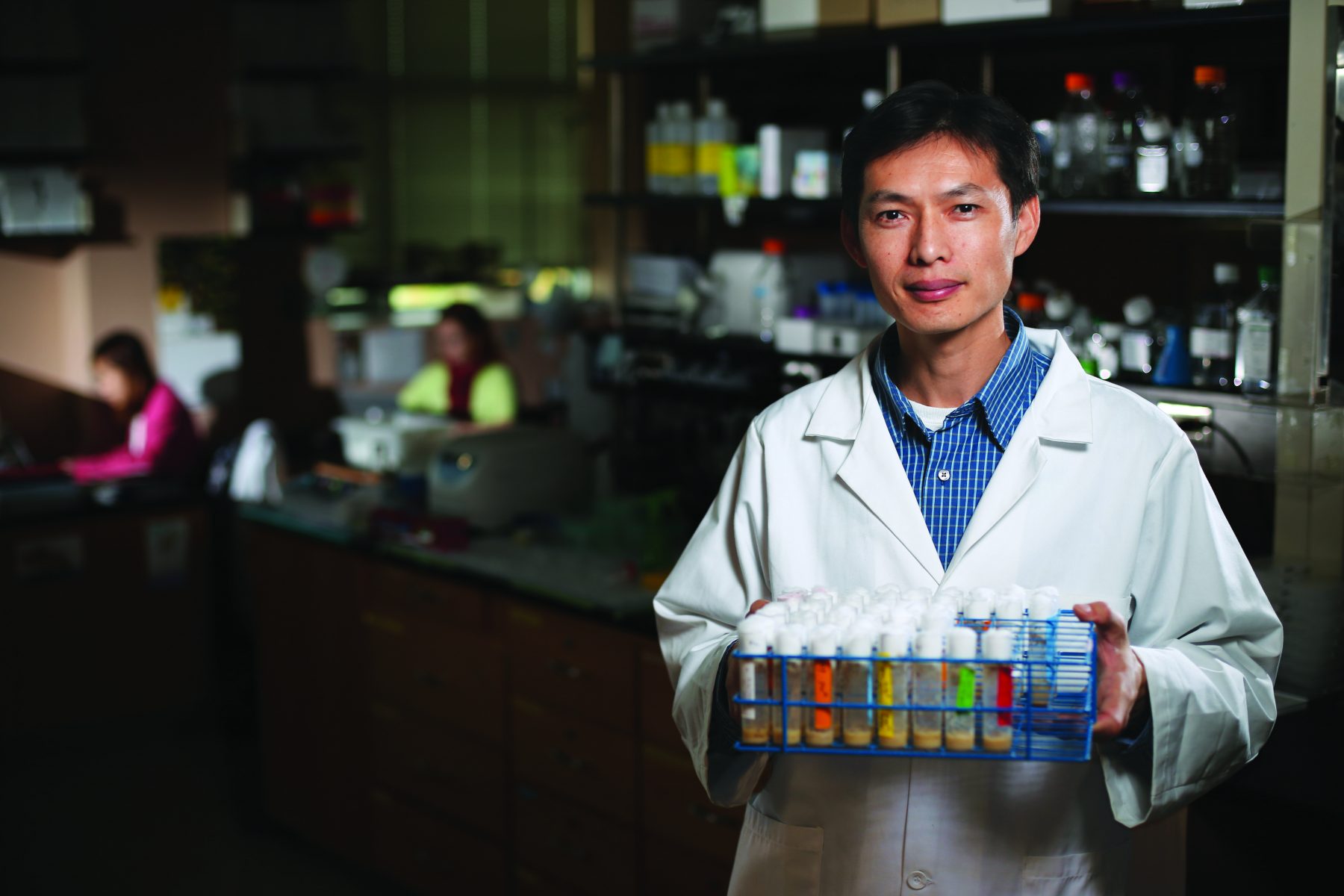

If your grandparents celebrated their 90th birthdays, there is a good chance you will, too. But what about those with families who do not have a history of longevity? Hua Bai, an assistant professor in genetics, development and cell biology, wants to help give everyone the same chance to live a long, healthy life.

The molecular differences in our genes decide, at least partly, whether we will live to 60 or 100.

He said aging is the biggest contributing factor to most diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease and heart disease. The goal of researching how we age is finding a way to prevent it. Instead of relying on pharmaceuticals to prevent or treat disease, Bai wants to stop our body’s ability to develop a disease in the first place.

“In the medical field, there has been a shift from promoting lifespan to promoting how we can improve and prolong our ‘healthspan,’” Bai said. “That means reducing the chances of developing a disease at old age, or even eliminating a disease altogether.”

Bai’s research takes a molecular look at the body’s ability – or inability – to fight disease as it ages. By looking at DNA code in genes, he has found hormonal signaling is linked to tissue function decline. “The same hormonal system that controls our developmental biology process also controls aging,” he said. “So the same hormone that promotes growth in our younger years tends to do harm in late life.”

That fickle hormone is insulin – the same one that impacts the metabolism of carbs, fats and protein and is associated with stress and decreased lifespan, as seen in diabetes and obesity. But insulin also plays an important role in aging, depending on our genetic makeup.

“When we get old, we develop an insulin insensitivity,” Bai said. “The body still produces enough insulin and it tries to maintain the glucose levels it needs, but sometimes, our cells do not respond to the insulin anymore. Since we all have a different genetic makeup, some of us are more prone to peripheral insulin resistance than others.”

Scientists around the world are busy trying to create medicines that will prevent or treat insulin resistance. Bai is looking at a different source for answers: fruit flies.

Unveiling secrets to long-term health

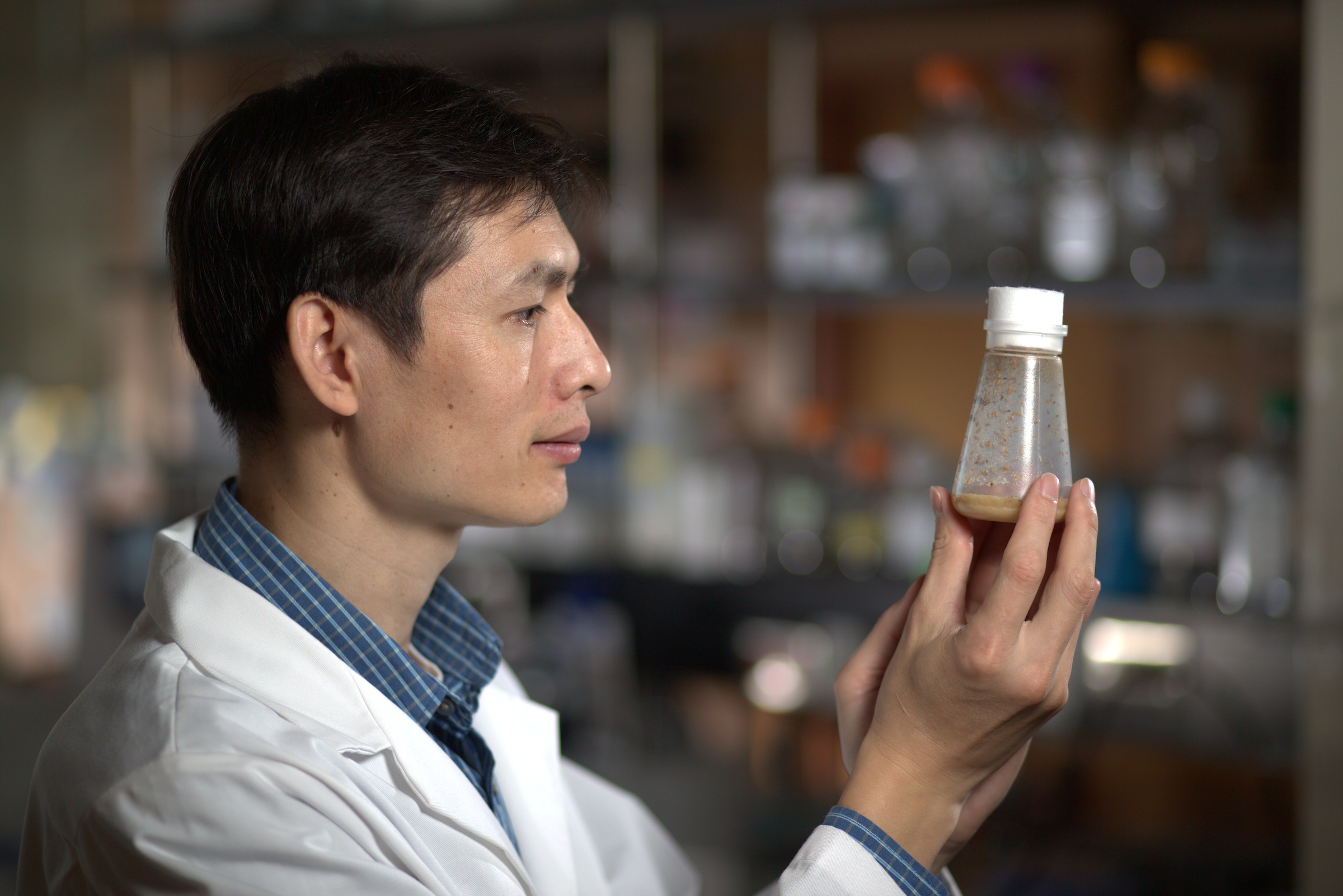

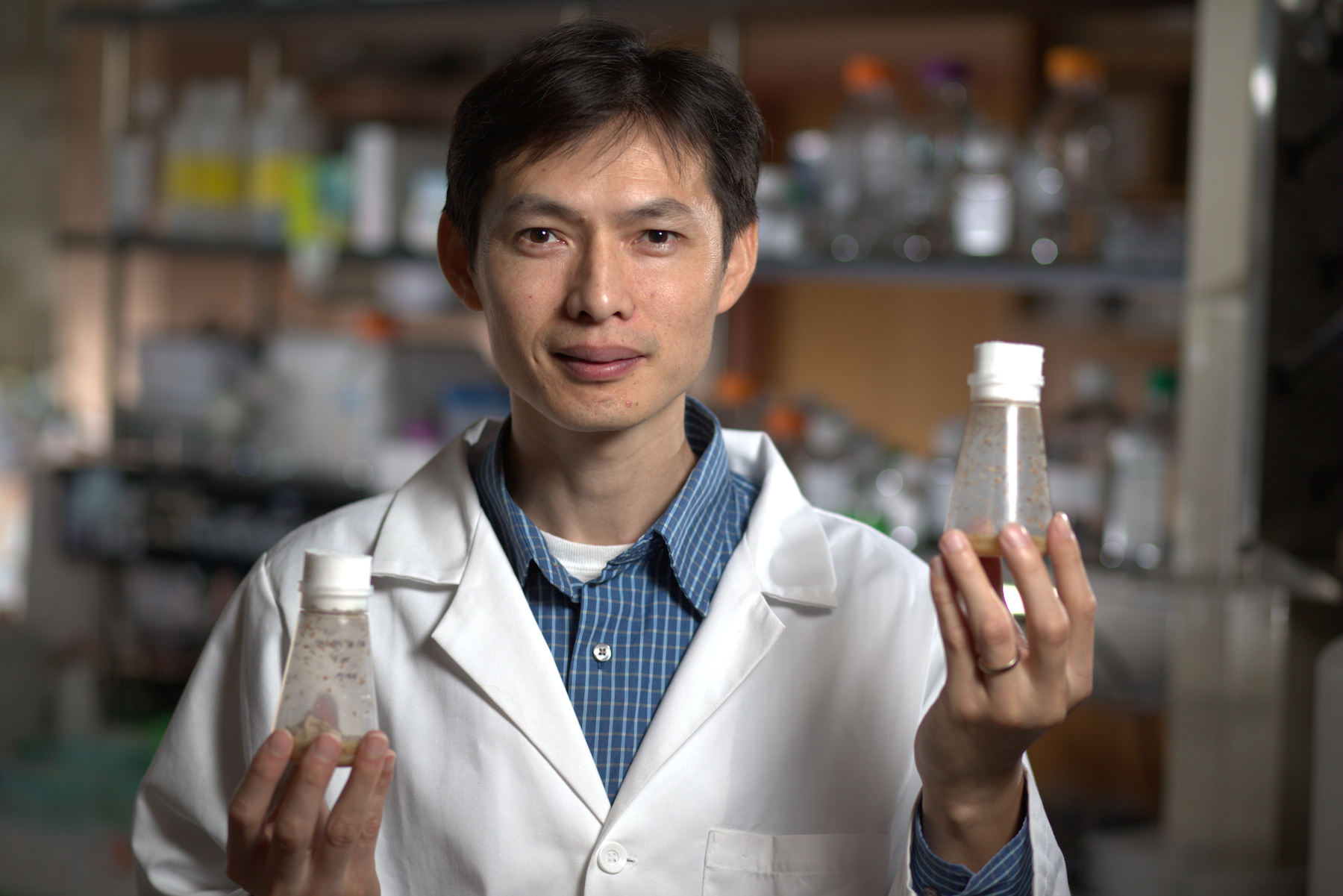

Fruit flies, a nuisance in kitchen counter fruit bowls, may hold secrets to improving our long-term health. The size of a grain of rice, the fruit fly’s entire genome is cataloged and well understood by researchers, allowing Bai to easily screen genes and identify potential gene mutations or variants implicated in human diseases.

“Right now, we are looking at fruit flies to understand age-dependent muscle function decline,” Bai said.

To do that, Bai and his team raise tens of thousands of fruit flies at varying stages of life. When a group of flies reach adulthood at five days old, they sort the flies according to their genetic makeup. Eye color, wing type, body hair and body shape all differentiate genetic makeup for “easy” sorting. Then, Bai and his team mutate the genes of certain flies, such as altering a fly’s sensitivity to insulin.

“We can do a lot of tricks to modify the genome,” Bai said. “And we find that if you have controlled insulin signaling, you’ll live longer. Or, at least that’s what happens for the fly.”

A fruit fly typically lives about 60 days. One of Bai’s modified flies has lived three months.

Creating a stronger, healthier heart

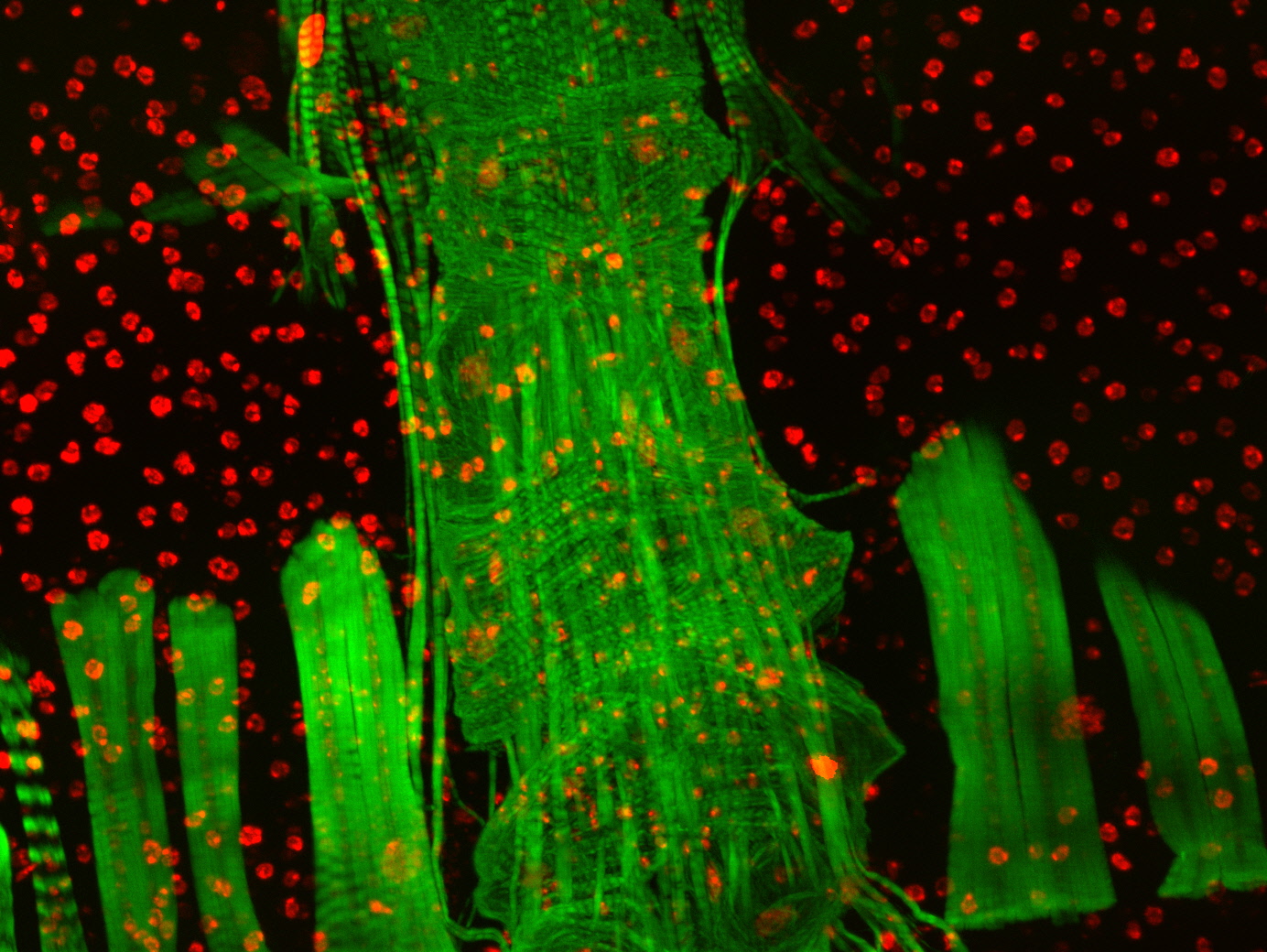

After modifying genomes, high-speed cameras are used to monitor muscle functions under various levels of stress or aging.

Research has already shown that a fruit fly’s heart can be used as a model for the human heart because fly hearts develop arrhythmias at old age (heartbeats that are too slow, too fast or irregular) similar to those that occur in humans. Bai carefully extracts the fly’s still-beating heart and monitors it with a high-speed digital camera attached to a microscope. Bai believes that by monitoring a fruit fly’s cardiac contractions, he can glean important information about how cells in the heart respond to stress and remodel with age.

While monitoring the fly’s heart muscle contractions, Bai also tracks down the ‘quality control machinery’ in the heart cells.

“We try to understand how heart cells use their quality control program to prevent cell damage and preserve heart functions with age,” Bai said. “We are interested in how the hormonal factors regulate cellular homeostasis during cardiac aging.”

What Bai calls a cell’s “quality control machinery” is the cellular recycling program called ‘autophagy,’ which has been linked to many age-related diseases.

“Aging research is very challenging but it could have monumental effects on the quality of life for humans,” Bai said. “It’s not just a matter of living longer, but living a longer, healthier life because we have the longevity genes that are able to protect us from disease and delay disabilities.”